There is a common argument made against linking the need for climate action with inequality and social justice issues, which goes: “Getting society off fossil fuels is challenging enough. So why make the task even more difficult by requiring our transition plans to rectify the other injustices of the world?”

The Green New Deal and other climate justice campaigns frequently encounter this position, often made by climate policy wonks and even some mainstream environmental organizations.

These climate policy purists are wrong. The rebuttal is two-fold.

First, these issues are deeply intertwined. People with lower incomes and less wealthy countries are more vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis. Those with higher incomes and wealth have greater GHG emissions. Conversely, many climate action policies impact lower-income people harder, and thus these impacts must be mitigated.

Second, it’s only by linking these issues that we win over and mobilize broad popular support. We can’t ask people to separate their fears about the climate crisis from the other affordability anxieties, economic pressures and systemic crises they face.

At a very basic level, inequality undermines trust that ‘we are all in this together.’ Many doubt that the task at hand will be undertaken in a fair manner. It’s hard to rally the public if many believe the rich are merely buying their way out of making change — fortifying their homes, walling off their communities or purchasing carbon offsets in the hopes that others will lower their actual emissions. Equally troubling is a cultural narrative that casts climate action as part of an elite project that sees the poor or those currently working in the fossil fuel sector as expendable.

My new book — A Good War: Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency — explores how Canada can rapidly decarbonize and rise to the climate crisis. But it’s structured around mobilization lessons from the Second World War.

Among the book’s key wartime lessons is that inequality is toxic to social solidarity and mass mobilization. A successful mobilization requires that people make common cause across class, race and gender, and that the public have confidence that sacrifices are being made by the rich as well as the working class.

As the Second World War got underway, one of Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s foremost objectives was to avoid mandatory conscription for overseas military service. This presented the King government with a formidable challenge: How do you convince hundreds of thousands of people to voluntarily enlist, to offer up their lives without duress?

To succeed in such an endeavour, a vital ingredient is social solidarity — a shared belief that everyone is in the fight. People need to feel confident that all are contributing according to their means, and making sacrifices in equal measure — the rich as well as the poor. And equally important, people need to know that the society that will emerge after their efforts will be a just and fair one. The social divisions fueled by economic inequality, racism and sexism are toxic to such efforts.

As Second World War mobilization efforts commenced, the governments of Canada, Britain and the United States were all concerned with preventing the type of outrageous war profiteering that had marked the First World War and eroded social solidarity generally and undermined military recruitment efforts specifically.

It wouldn’t do to have some people enlisting to fight and die, while others made a killing from a run-up in prices or from lucrative defence contracts. Britain was therefore quick to pass both an Anti-Profiteering Act and an Excess Profits Tax.

Canada did likewise. The King government instituted both wage and price controls during the war. Far less known is that Canada also imposed controls on profits. The profit margin on all government defence contracts was generally fixed at 5 to 10 per cent, which is certainly a nice guaranteed margin, but still a cap.

And it wasn’t just gouging on government contracts that Parliament sought to limit. The First World War highlighted that profiteering could happen in any number of industries, as war produced scarcity and new demands, and drove up prices. So, in the interests of ensuring solidarity across classes, all profits across the land were capped.

In order to do this, the government calculated the average profits for all businesses and corporations in Canada during the four years prior to the war. This then became a business’s maximum annual allowable profit for the duration of the war. All profits in excess of that cap were taxed at a marginal tax rate of 100 per cent.

In 1941, Finance Minister J.L. Ilsley said that, “No great fortunes can be accumulated out of wartime profits.” Similarly, in a speech to British Columbia lumbermen, forestry baron H.R. MacMillan said, “We must kill off that hangover from the last war — great profits. There can be no profits in this war to capitalists, labour or anyone else. Instead, there will be a sharing of losses.”

Looking back some 80 years later, this leadership seems hard to imagine. And it stands in stark contrast with the profiteering and wealth accumulation that has stained the months since the COVID-19 pandemic began. It’s virtually impossible to conceive of the corporate sector abiding such brash measures.

Yet as the above quotes illustrate, corporations during the Second World War not only acquiesced to such policies, but some of the country’s leading businessmen actively defended them to their peers. Clearly, there was a sense of common cause in the war that is not in evidence today. Not yet anyway.

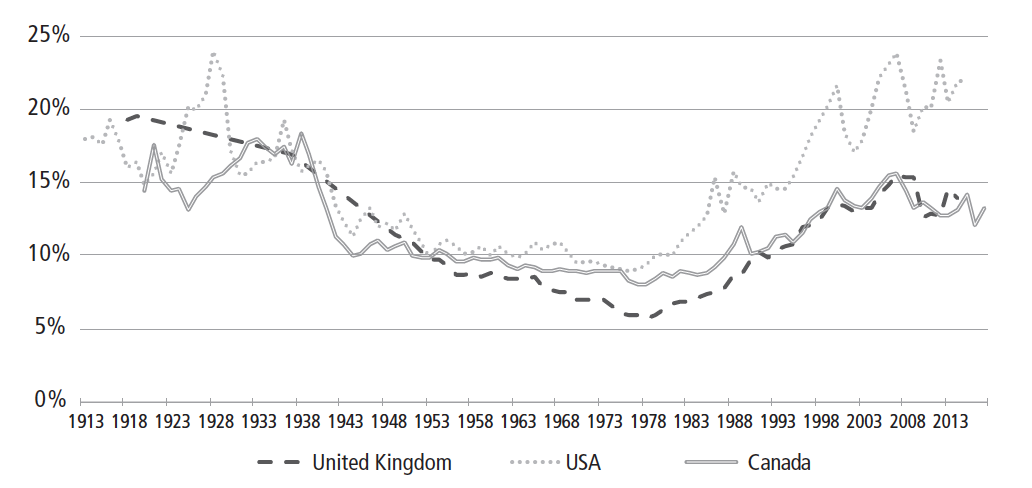

When I’ve spoken about the Second World War comparison employed by my book, I sometimes encounter the rejoinder that society was more cohesive back then. Yet interestingly, the state of inequality in Canada (as in the U.S. and United Kingdom) in the years before the war was remarkably high, with more than 15 per cent of income going to the wealthiest 1 per cent in all three countries. In fact, as the accompanying chart shows, the share of income going to the top 1 per cent in Canada reached its highest point of 18.4 per cent in 1938, the year before the war.

But as also seen in the chart of top 1 per cent income shares, the war fundamentally jolted income distribution and marked the start of a three-decade period of much greater income equality. Since the mid-1980s, however, all three countries have witnessed a U-turn, with the share of income going to the richest 1 per cent moving back toward pre-war levels (although Canada has seen a slight decline since the 2008 recession).

It’s striking that in all these countries, early mobilization efforts confronted a reality of stark income inequality — just as we do today — yet all emerged from these transformative experiences as more equal societies.

(This should, of course, not be overstated: the society that prevailed during and after the war remained deeply sexist and racist, still denying franchise to Asian and Indigenous people in Canada, turning away Jewish wartime refugees and shamefully interning more than 21,000 Japanese Canadians.)

Canada’s war experience also fundamentally transformed people’s expectations of what they were due and what could be accomplished together. The Second World War saw the introduction of Canada’s first major universal income security programs. Needing to secure social solidarity across society, the King government instituted unemployment insurance in 1940 and the universal family allowance in 1944. And the famed Marsh Report, which would lay out the architecture of what would be the post-war modern Canadian social welfare system, was written during the war.

The point in recalling all this — as we face today’s threat and the need for mobilization — is to appreciate that effective mobilization isn’t merely about building more planes and tanks, or today, wind turbines and solar panels. It requires policies that fulfill a promise that we will better look after one another, that we will offer good jobs and income supports to all, and that people will be treated with dignity and fairness. When you’re asking people to share in a great undertaking, that’s how you keep everyone on the bus.

For years now, various public opinion polls have highlighted a paradox: respondents indicate high levels of concern regarding climate change and strong support for policies that would reduce GHG emissions, yet low levels of willingness to personally pay for climate action.

But there’s no great mystery to this mixed response. In polling I commissioned for my book research from Abacus data in the summer of 2019, affordability was named as the top concern of Canadians, just ahead of climate change. That only stands to reason; it’s a more immediate concern to most people. Hence the powerful need to link these issues.

When we do so, the appeal is dramatic, far surpassing the levels of support for any one political party. As the Abacus poll revealed, when Canadians were given a short explanation of the Green New Deal — describing it as an ambitious vision for tackling the twin crises of climate change and inequality — it proved immensely popular, supported by 72 per cent of Canadians surveyed.

Another key finding from the Abacus poll: the more a bold and transformative climate plan is seen as linked to an ambitious plan to tackle inequality, economic insecurity, poverty and job creation, the more likely people are to offer their support.

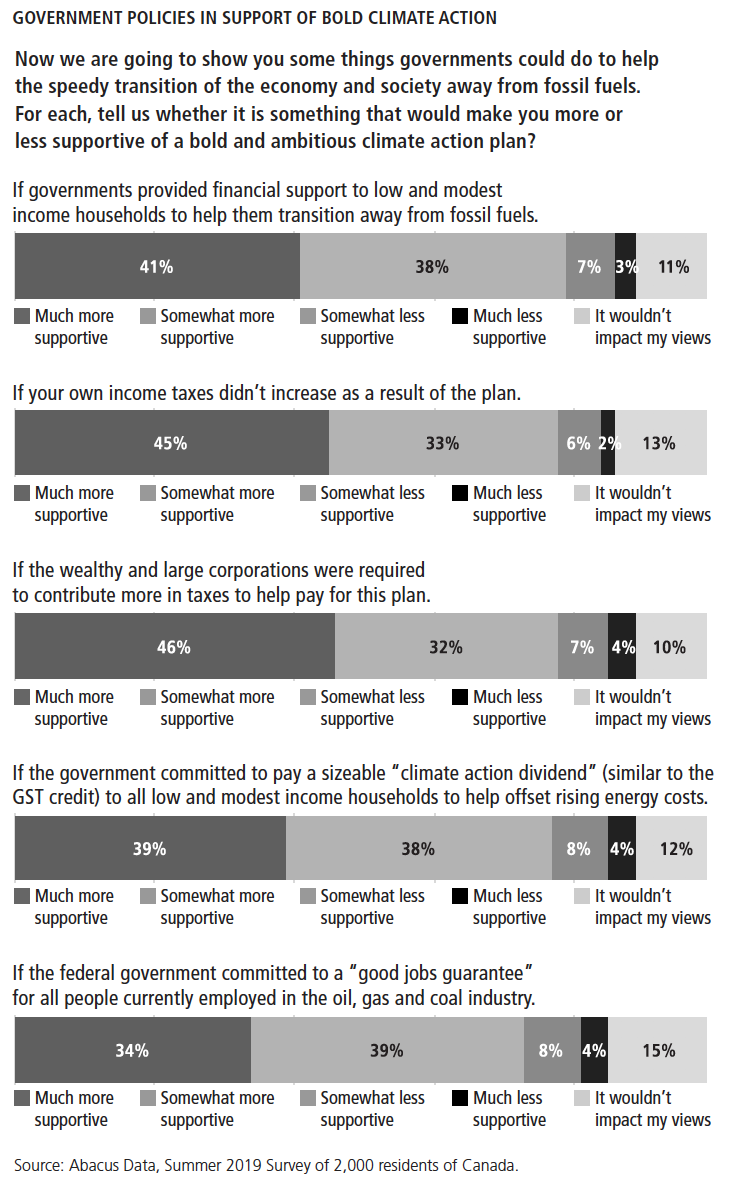

The poll listed five policy actions that could help with the transition — including extending income and employment support to those more vulnerable during the transition, and increasing taxes on the wealthy and corporations to help pay for the transition — and asked people if such policies would make them more or less supportive of bold and ambitious climate actions. Those five policy options and the responses are shown below.

As evidenced, if the government provided financial support to low and modest-income households to help them pay for the transition away from fossil fuels, 79 per cent of people became more supportive of bold climate action — 41 per cent said “much more supportive,” while a further 38 per cent say they would be “somewhat more supportive.”

Similarly, if the government increased taxes on the wealthy and corporations to help pay for the transition, 78 per cent of respondents became more supportive of a bold climate plan — 46 per cent much more supportive, and a further 32 per cent somewhat more supportive.

And if the government were to commit to a “good jobs guarantee” for current fossil fuel workers — a signal that the government was ready to actively help with a just transition plan for workers — 73 per cent became more supportive of ambitious climate action.

The takeaway from these results is clear: When ambitious climate action is linked to tackling inequality and job insecurity, support dramatically increases

Inequality isn’t only a moral problem — it’s a practical barrier in getting to carbon-zero. Runaway wealth is associated with runaway emissions, while poverty and inequality — in all their dimensions — will be exacerbated by climate policy, unless this reality is explicitly recognized and tackling inequality is built into the design of climate action measures.

High levels of inequality undermine social cohesion and promote social divisions, rather than building the social and political trust needed to chart a future based on a sense of shared fate. If climate policies aren’t perceived as fair, public support will not be sustained, and political determination will shrink accordingly.

The more a robust climate action plan is linked to an exciting plan to tackle poverty and inequality, along with a hopeful and convincing jobs plan, the more we maximize public support. Plus, it’s the right thing to do.