Last month, the School of Industrial and Labor Relations (ILR) at Cornell University released the annual report of its Labour Action Tracker (LAT). Once again, the report shows a considerable growth in strike activity in the United States.

The annual release of the LAT report has become a vital resource for gauging the level of strike activity in the U.S. Since the ILR School launched the LAT around three years ago, it has recorded a more than 77 per cent growth in strikes across the American economy.

Without the LAT, we wouldn’t know about many of these job actions.

Due to funding cuts first made during the Reagan Administration, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) only tracks work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers. In other words, the American agency officially tasked with compiling strike, wage and other labour-related data leaves most strike action uncounted and largely unrecognized. Quite obviously, rigid selection criteria and inaccurate and incomplete data make it difficult for policymakers and labour practitioners to gain a clear picture of workplace conflict in the U.S. The LAT was created to fill this data gap and correct the record.

Researchers at the LAT generate their data using a variety of sources, including media reports and social media. They also collect information on the size, duration, industry and demands of all strikes, and run each job action through a rigorous verification process. As the report notes, the LAT may undercount strikes due to this verification procedure. Yet even with this caveat, the researchers at the ILR School report strike figures far in excess of those recorded by the BLS.

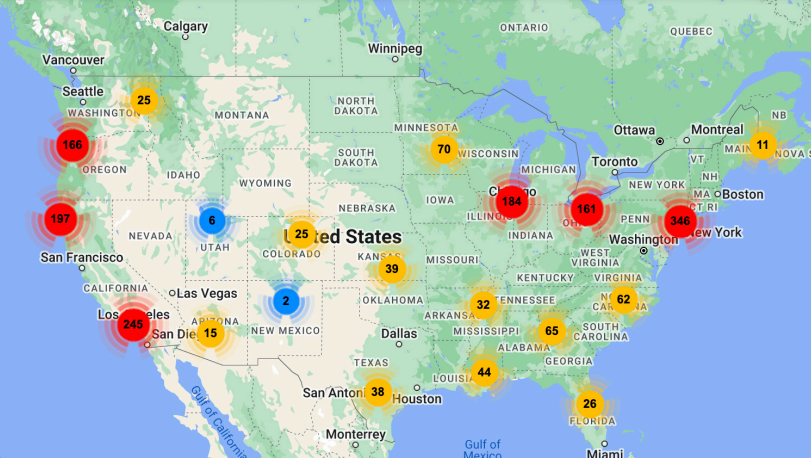

According to this year’s report, the LAT recorded 470 work stoppages (466 strikes and four lockouts) in 2023. By contrast, the BLS lists 33 “major work stoppages” in 2023, up from 23 the previous year.

Approximately 539,000 American workers went on strike across these 470 work stoppages last year, up considerably from 224,000 workers in 2022 and 140,000 in 2021.

In 2023, work stoppages increased by 9 per cent from the year prior, according to the LAT. After slightly revising last year’s figures, ILR researchers recorded 433 work stoppages (426 strikes and seven lockouts) for 2022.

However, what is most notable in 2023 is the growth in what the ILR School calls “strike days,” or what in Canada are generally called “person days lost.” Last year, there were 24,874,522 strike days recorded in the LAT’s data, an increase of 459 per cent from 2022. In part, this growth in strike days is the result of several large strikes by well-established unions.

On the other hand, perhaps one of the most important features of the LAT concerns its attention to small strikes, particularly among workers who aren’t members of a union. As I’ve argued before, the ability of non-union workers to strike in the U.S. is one area where American labour law offers advantages not available to Canadian workers.

According to the ILR’s report, the number of non-union workers on strike has declined over the last three years from nearly 252,000 in 2021 to 65,167 in 2023. Yet even with this decline, strikes by non-union workers still accounted for 22 per cent of all work stoppages in 2023, though this has fallen from 31 and 37 per cent in 2022 and 2021, respectively. That more than one in five American strikes are organized by non-union workers is notable.

By contrast, the ILR researchers point out that the number of work stoppages involving demands for a first union contract continues to grow, more than doubling between 2022 and 2023. Last year, 74 out of 470 strikes (nearly 16 per cent) included a demand that an employer bargain a first contract.

On the one hand, first contract demands demonstrate workers’ resolve to have their issues met through collective agreements. On the other hand, that so many workers had to strike for a first contract is yet more evidence that American employers will do everything they can to avoid bargaining one. Unfortunately, U.S. labour law gives them wide latitude to resist bargaining and exhaust new unions.

While non-union workers’ strike activity fell in 2023, this was more than offset by striking workers in union strongholds such as auto manufacturing, healthcare, education and film and television production. Indeed, a large portion of the growth in both total work stoppages and the number of workers on strike was accounted for by the United Auto Workers’ “stand-up strikes” at the Big Three, job action by unions at Kaiser Permanente, the walkout of the Los Angeles teachers’ union, and of course, the actors’ and writers’ strikes in Hollywood.

All told, workers involved in those four work stoppages accounted for roughly 65 per cent of strikers in 2023. High-profile labour actions from auto to Hollywood not only boosted the strike figures but also brought popular attention to the cause of labour throughout the year.

Not all American strikes in 2023 took place in highly unionized industries, however. As in 2022, accommodation and food services made up the largest share of work stoppages, at 33 per cent of the total. At the same time, this sector accounted for only 6 per cent of all striking workers. Small workplaces in this industry have emerged as ‘strike prone’ in recent years. Yet, as the report notes, Starbucks Workers United and SEIU’s Fast Food Campaign accounted for 82 per cent of strikes in accommodation and food services.

Other interesting patterns are noted in the LAT report as well. As in 2022, the three most common demands across strikes were better pay, improved health and safety, and increased staffing. As inflation continues to bite and cost-of-living challenges compound, workers across sectors and workplaces are using the strike to fight back.

Last, the average duration of the work stoppages recorded by the LAT remains quite short. Sixty-two percent of all strikes lasted fewer than five days in 2023. This is to be expected given the industrial composition of the data. Short job actions are much more common among non-union or recently unionized workers in small workplaces.

The ILR’s report is interesting and instructive reading, for both American and Canadian readers. It does raise a question though: How does Canada’s strike data compare?

Statistics Canada does a much better job of tracking work stoppages in this country than the BLS does in the U.S. (though StatCan is by no means perfect either). StatCan’s figures for 2023 are only available until the end of November. This is important because the data don’t include the Quebec Front commun strike, the impact of which will be massive. Nevertheless, last year’s data make an interesting comparison with the U.S.

Between January and November of 2023, there were 133 work stoppages in Canada. Although the number of workers involved in strikes has declined every year since 2020 — down to 169,102 last year — “person days lost” increased appreciably to well over 2.3 million. The reason for this is that strikes were on average considerably longer last year, as I’ve discussed before.

Keep in mind that the American labour force is nearly eight times larger than Canada’s. Whereas the U.S. has a total labour force of more than 167 million workers, Canada’s workforce is roughly 21 million.

With a workforce considerably smaller, Canada still recorded close to a third as many strikes as well as workers on strike as the U.S. When you remember that non-union workers can’t strike in Canada, the difference in strike data is even more appreciable.

Quite obviously, Canadians shouldn’t rest on our laurels. The American labour movement has taken a beating like no other. But what the LAT’s annual reports continue to show is that workers in the U.S. are fighting back, and more so each year.

Canadian workers should do the same.

Recent Class Struggle Issues

- March 18 | Card-Check Union Certification In B.C. Has Been A Major Success

- March 11 | Doug Ford’s Failed Wage Restraint Measure Has Cost Ontario Billions

- March 4 | Collective Bargaining Rights Are Being Systematically Undermined

- February 26 | An Interview With The New President Of CAPE