Earlier this month, the National Supply Chain Task Force, which was convened by the federal government in March to study ways to improve Canada’s supply chain, released its final report. For the most part, the document is rather unremarkable. Yet buried within the report’s technical recommendation was a telling admission: the neoliberal push of the last decades to deregulate and cut “waste” has also undermined both governments’ and capital’s long-term planning capacities. The brittle supply chain that so easily snapped during the pandemic was the entirely predictable consequence of this deregulation, and the inflation we’ve experienced since has been capital’s undeserved windfall.

But don’t expect much of what the task force recommends to address these issues. Instead, they chose to make several policy suggestions that should receive the ire of workers.

The mandate of the National Supply Chain Task Force centered around: making recommendations to Minister of Transport Omar Alghabra on ways to improve the fluidity and operation of Canada’s supply chain; identifying areas where technological improvements can aid in supply chain coordination; collaborating with national and international experts and “partners” in improving the supply of goods and services in Canada. After continued supply disruptions caused by the pandemic and over a year’s worth of inflationary consequences, business experts were tasked with drafting ways to ameliorate the national impacts of an overstretched global system of production and distribution.

While labour organizations were consulted during the task force’s work, labour had no formal position on the body. No unions representing workers in any of the affected industries — airlines, port terminals and long-shoring, freight rail, interprovincial shipping and transportation — were given a seat at the task force table. Rather, this was an affair oriented solely around the needs of employers. Consequently, the recommendations contained within the final report clearly reflect labour’s lack of representation on the task force.

Major recommendations include immediate “operational” and “governance” shifts, such as loosening regulations to ease port congestion and expedite cross-border shipping, as well as creating a “supply chain office” to coordinate a national strategy to improve Canada’s shipping network. Long-term action items include major infrastructure investments, especially to digitize port terminals and allow better coordination throughout the supply chain, and of course ways to address mounting labour shortage issues, particularly in the long-haul trucking sector.

The report’s authors identify “rapidly changing trade patterns, human- and climate-caused disruptions, shifting geopolitical risk, and increased consolidation in major transportation modes” as urgent challenges confronting industry and government. Yet, the report also praises the “economic deregulation of transportation policies over the past 30 years [that] successfully unleashed the power of competitive, market-based forces across the sector” — the very market forces that have undermined the ability of governments to effectively plan and coordinate a national economic strategy.

The pandemic caused such massive disruptions to the supply chain and the pool of available skilled workers precisely because both have been stretched vanishingly thin by a lean-production model meant to eliminate all “waste” (i.e., any “unproductive” oversupply). When the international supply chain was fractured due to public restrictions and economic contraction, there was simply no slack to ease the shortages. Rather than improve the “efficiency” of global and national logistics, lean production and deregulation undermined the capacity of firms, governments, and society more broadly to withstand supply chain disruptions, such as those necessitated by COVID-19 public health restrictions.

The situation in long-haul trucking is a telling example. The deregulation of international and inter-provincial trucking since the 1980s has hollowed out the industry and created a labour standards nightmare. After the United States deregulated trucking through the 1980 Motor Carrier Act, Canada soon followed suit. These combined changes led to a proliferation of small firms and the rapid de-unionization of the trucking industry, which helped undermine the pay and working conditions of truck drivers across the sector. It’s within this policy environment that a “labour shortage” of long-haul truckers has emerged.

As the task force authors note, “Statistics Canada-reported vacancies for qualified truck drivers reached an all-time high of 25,560 vacant positions from January to March 2022.” Moreover, deregulation has contributed to rampant misclassification and labour standards violations in trucking. Misclassification of truckers as “independent contractors” is now so widespread that last year the federal government launched a pilot project to try to crack down on firms engaging in this unlawful practice. According to research using data from the Labour Program of Employment and Social Development Canada, which enforces federal labour standards, nearly 80 per cent of labour complaints received between 2006 and 2021 came from workers in the federally-regulated trucking industry. This is an industry that is also becoming structurally dependent on temporary foreign workers whose precarious citizenship status makes them prime targets for exploitation. The task force nevertheless recommends expanding use of temporary foreign workers.

The above deregulation has also led to what the report identifies as a lack of coordination and planning across logistics supply chains. As the authors note later, “Global adoption of practices such as ‘just-in-time’ delivery and of transportation systems built to maximize efficiency and minimize costs created a transportation supply chain unprepared for disruption.” In response, the task force would like to see a revision of the mandate of the Canadian Transportation Agency so it can “keep market forces in check.” As the report continues, “The regulator should have the authority to address unfettered competition that negatively affects the national public interest.” However, this is hardly a reform that’s up to the task of responding to the problems generated by deregulation, which make national coordination difficult and increase the prevalence of labour standards violations. The task force seems to want a market-driven system without its inherently negative and disruptive repercussions.

The report further identifies what it considered to be a long-term problem of under-investment in key supply chain infrastructure throughout Canada, including roads, ports, communications systems and rail and air transport infrastructure. For example, the authors note that the ratio of infrastructure investment to trade volume has been declining since the 1980s. As Canada’s trade volume has increased, public and private investment in infrastructure has not kept pace.

The report’s authors therefore call on both public and private sector actors to address this investment shortfall over the immediate and long term. The solutions they advocate are heavily dependent on “digitization” and the enhanced use of data and automation. The task force would like to see “digital data hubs” created to better integrate and coordinate ports, shipping and other supply chain infrastructure, as well as greater investment in automation, particularly at ports. The risk here is that government subsidies will simply pad the profits of corporations throughout the supply chain, rather than compel them to make meaningful investments. For example, the task force suggests that airport rental fees should be waived by 50 per cent to allow airport authorities — already a form of public-private partnership — to make needed capital investments.

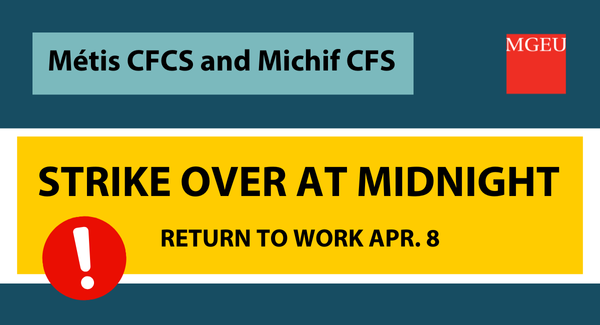

As concerned as the task force seems to be with labour shortages (particularly in rail and trucking), it also registered its apprehension about the supply chain consequences of “labour action,” i.e., strikes or threats of strikes. The report claims: “[S]trikes at Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) in 2018 and 2022, Canadian National Railway (CN) in 2019, the Port of Montreal in 2021, and a two-day work stoppage at CP in 2022 all affected how logistics and supply chain decision-makers and international businesses view Canada’s reliability as a place to do business.”

In response to the supposed threat of workers exercising their rights to free collective bargaining and striking, the report’s authors wish to see the government “protect corridors, border crossings and gateways from disruptions to ensure unfettered access for commercial transportation modes and continuity of supply chain movement.” The report therefore recommends creating “risk management strategies” to plan for everything from climate-related disruptions, “human-caused mischief” and labour disputes. In other words, governments and firms should plan for ways to undermine and erode the power of work stoppages.

Perhaps most strikingly, on the labour relations front the task force recommends that, “The Minister of Labour should urgently convene a council of experts to develop a new collaborative labour relations paradigm that would reduce the likelihood of strikes, threat of strikes, or lockouts that risk the operation or fluidity of the national transportation supply chain.” Though I doubt the federal government will entertain such a proposal, that a task force of “experts” would recommend overhauling labour law to make it more “collaborative” (i.e., employer-friendly) in this way is nevertheless troubling. The federal government’s heavy-handed use of back-to-work legislation against port, rail and postal workers is bad enough, but apparently not sufficiently draconian for the task force. The Teamsters union has already voiced its opposition to this worrying recommendation.

The task force is evidently also worried about “political” disruptions outside of formal labour disputes. Although they likely have in mind “mischief” such as the so-called “Freedom Convoy” border blockades, the authors’ call for enhancing the ability of law enforcement to “preempt” and prevent the impediment of critical supply chain infrastructure is worrying, to say the least. Such enhanced law enforcement capacity would pose a heightened threat to rights surrounding political protest, particularly of Indigenous communities seeking to protect lands and resources.

After decades of deregulation, attacks on labour and underinvestment — all exposed by the pandemic and subsequent supply chain crisis — employers and their representatives seek more of the same. Reading between the lines of the National Supply Chain Task Force report, it’s easier to see how unleashing the very “market forces” the authors praise has also created the problems they identify.

Of course, they wouldn’t see it this way. A labour-based supply chain agenda that puts workers’ rights and the public good ahead of corporate profit is the only antidote.