D.J., who lives in Calgary, Alta., first heard that the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB) was ending on Oct. 23 through an attendee at her local Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) group.

“I thought, oh my god, that’s a little too soon for us,” D.J. told The Maple.

D.J. works from home as a director of a small non-profit that works with schools, and asked that her full name not be used because she did not want to be seen as disparaging her organization. Her husband receives AISH, and D.J. currently works 10 hours per week, down from 22 in pre-pandemic times.

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland announced last month that CRB — along with the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) and the Canada Emergency Rent Subsidy (CERS) — would not be renewed, and instead replaced with a smaller benefit that will only be disbursed to workers who lose their jobs or have their hours cut because of government-ordered COVID-19 lockdowns (there are currently no lockdowns in place in Canada).

D.J. said she received CRB to supplement her collapsed income for 27 “eligibility periods” (54 weeks) — the maximum allowed under the program. Her organization did not qualify for CEWS, she said.

The CRB — which paid $900 every two weeks to eligible workers or self-employed individuals for the first 42 weeks of the program, before payments were reduced to $540 in July — replaced the earlier Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB).

Now, with no support, D.J. and others in similar situations face an uncertain future.

“We’re a little stressed out right now,” said D.J., adding that there is little prospect of her work returning to normal anytime in the near future.

“We haven't got any in-person events really happening, because we don't know where we're at in Alberta,” D.J. explained. “We're in the fourth wave and our (provincial) government has not been exactly the best decision-makers throughout this.”

D.J. and her husband did not use their pandemic benefits to eat Cheezies and watch cartoons, as one United Conservative Party MLA suggested back in September 2020.

Even before the pandemic, the couple struggled to make ends meet, particularly as D.J.’s husband’s AISH payments are clawed back if D.J. makes more than $2,612 per month.

The CRB was exempt from AISH clawbacks until June 30, meaning recipients were able to collect both benefits in full. During that time, D.J. said, “we were able to pay all the bills and actually eat. It’s the first time in almost 20 years that my husband and I have actually been able to live like human beings.”

“We've always had to go to the food bank, or we've been scraping, having to buy really cheap stuff,” she added. “It's not very healthy, especially for a diabetic.”

D.J. — who has type two diabetes and a genetic condition that makes full-time, in-person work impossible — said her own health challenges mean that she may also need to apply for disability benefits soon. CERB, which she also received, enabled her to pay $367 per month for a continuous glucose monitoring device, which allowed her to track her blood-sugar levels.

When payments were reduced under the CRB system, however, D.J. had to make do without that device. Now, she must return to her pre-pandemic struggles without the support of either benefit.

Hundreds Of Thousands Of Workers In Limbo

D.J. and her husband are not alone in their difficult situation.

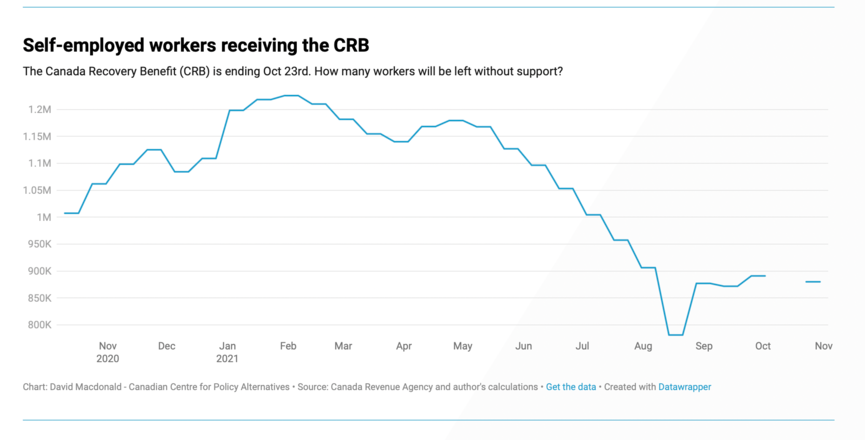

In a recent analysis, David Macdonald, a senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, wrote that the termination of CRB cut off 880,000 workers from the benefit. While several other pandemic programs saw a significant decline in uptake in recent months, the CRB did not.

As well, government documents obtained by The Canadian Press last month showed that the majority of those who received CRB were repeat or continuous recipients, indicating a strong level of dependence on the program.

Macdonald told The Maple that CRB was set up for self-employed workers who did not qualify for employment insurance, meaning there are no other means of government support available to them.

As well, he explained, there is no guarantee that those who can work will be able to find suitable employment in the near future.

“The economy still has not completely recovered,” said Macdonald. “We've recovered the number of jobs that we had in February 2020, but because the population has grown, we're not at the same level of employment rate, because there's more people looking for jobs.”

“In key industries, restrictions remain,” he continued. “Those industries can't fully reopen for a variety of reasons related to public health and government mandates, and so there's still plenty of people who can't restart their previous jobs.”

Macdonald pointed out that no one is calling for the cancellation of EI provisions for eligible workers, and yet there is no backup safety net currently in place for self-employed workers.

“I think one of the main recognitions of the CERB program was that (self-employed workers) is an important and growing portion of the labour force in Canada, and that it should be covered as part of a jobless benefits scheme,” said Macdonald.

He noted that the Liberal government has committed to setting up a jobless benefits program for self-employed workers in January 2023, but this timeline means former CRB recipients have no support until then, even as businesses continue to receive targeted support following the end of CEWS.

Notably, said Macdonald, the term “self-employed” includes misclassified “gig economy” workers, and those who work as independent contractors.

Whereas the problem of misclassified gig workers being denied EI benefits could be solved by forcing employers to recognize their workers as employees, Macdonald explained, the problem is more complicated for the latter group.

“It wouldn't be hard to continue the CRB for a couple more months. The challenging part is: How do you get it in the long term to be somewhat sustainable?,” said Macdonald.

Artists Left With Few Opportunities

One of those self-employed workers now left without benefits is Arthur McGregor, a folk musician based in Kemptville, Ont., and his wife, Wendy Moore, who together perform musical theatre as the Celtic Rathskallions.

Before the pandemic, the duo earned most of their income performing in public schools and seniors homes across Canada, as well as playing shows in the United States and Ireland. McGregor also plays in another duet, has a musical solo project and is vice president of Local 1000 of the Canadian Federation of Musicians (CFM).

McGregor told The Maple that the last in-person show he and Moore played was a few days before St. Patrick’s Day 2020 — just before the pandemic was declared. All future in-person shows were cancelled, and it took weeks before online performances were arranged.

McGregor said online performances are a poor substitute for the real thing. “It earns a bit of money, but it doesn't earn any enjoyment — musical enjoyment — and schools have still not opened up from that level of performance,” he explained.

Both McGregor and Moore received CERB and CRB throughout the pandemic. “There was no question it was a lifesaver,” said McGregor.

During the pandemic, McGregor explained, the duo have cut down on day-to-day spending as much as possible, with the benefit of not having to pay the steep travel and accommodation expenses associated with touring.

“CERB was able to easily meet our expenses,” said McGregor, who added that the couple were able to save some money during that time. They now must use those savings to bridge the gap between the termination of CRB and the return of in-person performances — whenever that might happen.

“I'm confident that things will come back,” said McGregor, “but they're not going to come back over the short run in the music industry.”

In the meantime, things remain uncertain for McGregor and Moore, who are searching for other jobs in the industry.

“Schools are not, I don't believe, thinking really heavily about bringing in musicians to do this kind of thing — musical theatre, songwriting workshops and stuff like that,” said McGregor, who noted that while various government programs have offered funding for venues and festivals, as well as discounts for schools to book musicians, that money doesn’t necessarily end up in the pockets of musicians.

McGregor said the Rathskallions recently received a callout for next year’s Ottawa Bluesfest, scheduled for July 7-17 — but that will only happen if public health orders allow the event to go ahead.

“If six months down the line, it's still an ‘if,’ the interim doesn't look very good, either,” McGregor explained. “So I honestly don't know how this is going to play out. It's so hard to try and figure out what the future looks like.”

While CFM works hard to advocate on behalf of its members in difficult times, McGregor said, the union does not have nearly as much clout as major business groups that are also lobbying the government for support during the pandemic.

“There isn't the strength of organization in the artistic world as there is in the business world,” McGregor explained. “That's just a given, even with a good union.”

NDP MP Says Constituents In 'Difficult' Situation

Jenny Kwan, the NDP MP for Vancouver East, told The Maple she is also concerned about the impact the federal government’s decision not to renew CRB will have on the arts and culture sector. According to Kwan, her riding has the highest per capita number of people employed in that sector in the country.

“The pandemic has hit them hard,” said Kwan, who explained that she has spoken to constituents who have seen live bookings dry up during the pandemic fourth wave.

“With the CERB and CRB ending, it places people in that very, very difficult situation,” she added. “And it is a situation where people are saying, how are they going to make rent?”

Kwan noted that one of CRB’s eligibility requirements was that all recipients must be, per the program’s website, “seeking work ... either as an employee or in self-employment,” and “have not turned down reasonable work.”

“The assumption that they might just be looking to collect the CRB without working, that's simply untrue,” said Kwan. “There are still a lot of people who are still out of work and unable to secure employment.”

“What we have to do is pull together to support people through these difficult times, as we work to re-adjust ourselves,” she added. “There are some industries that have not yet bounced back, and we need to recognize that those workers are equally impacted, and they continue to need to be supported.”

As well, Kwan said the federal government must ensure that seniors who collected CERB and CRB do not lose the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), as some have found they have been cut off from the program after receiving pandemic benefits.

“There's some seniors who have already told me that if the government doesn't address this issue, they are going to be without a home,” said Kwan.

No CRB, And No Job Opportunities

D.J. said the fact that she and others like her relied on emergency benefits to cover basic expenses demonstrates that the current economic reality — even before the pandemic — is not sustainable.

“The rhetoric just serves to make people feel like they're lazy, or like they just don't want to work,” she added. “We need to put the tax dollars to work for all the people, whether it's universal basic income (or something else).”

In the meantime, she said, “it's probably going to be a game of okay, what bill doesn't get paid this month so that we can eat, because that was what we were doing before.”

D.J. thinks the idea that the benefits needed to be cut to send people back to work amid “labour shortages” is based on an unrealistic “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality that ignores the material conditions that she and others face.

“The system that we currently use is really not working all that well,” she explained. “The way they've been measuring how well the economy is doing is by how well the large corporations are doing. They never look at how the people are doing.”

Melissa Burkhart and her mother, Pat, who both live in Winnipeg, know all too well what it’s like to feel that their wellbeing is overlooked by decision-makers in Ottawa.

Melissa has fibromyalgia and receives disability support, which she said barely covers food, rent and basic medications, but not extended treatment. She lives with Pat, who received CERB for the first three months of the pandemic after being laid off from her job at a lottery kiosk, before finding work at a hotel.

“I couldn't have paid my bills without (CERB),” Pat told The Maple.

Pat was then laid off multiple times, most recently in August, and has received employment insurance payments since. However, she was recently notified by Service Canada that her EI payments will soon end.

Without the prospect of any additional government support or benefits, Pat said the future is “bleak,” as she has not been able to find a job, despite sending out up to five applications per week. She believes her older age explains why she has not had any responses lately.

“Without any extra benefits, I don't know what we're going to do,” said Pat.

“I don't know how we’ll manage without it,” Melissa added. “Neither one of our incomes without it is livable.”

Pat said that hearing recent media reports about “labour shortages” and employers claiming that they were struggling to find workers because of pandemic benefit payments makes her angry.

“I want to work, and I think most people want to work,” she said. “I don't think it's correct when people say that. I find it very upsetting.”

“They're saying these things coming from a place of power, from a place of privilege, where they've never been in this sort of a situation, where they've been desperate,” Melissa added.

Alex Cosh is the managing editor of The Maple.