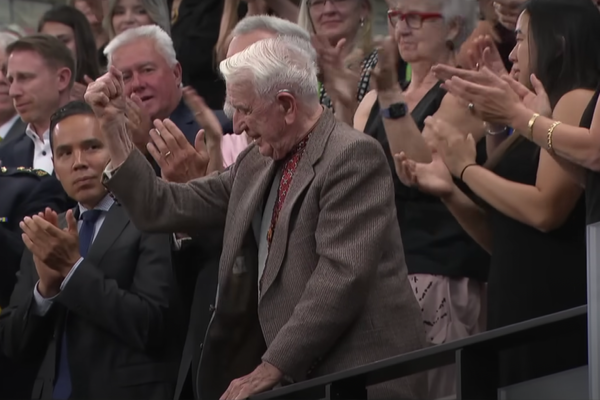

Five months after Canadian members of Parliament gave two standing ovations to Yarolsav Hunka, a 98-year-old Waffen SS veteran who was introduced as a “Canadian hero,” last fall’s Nazi Parliament scandal continues to prompt difficult questions for the Trudeau government and Canadian institutions.

Most recently, the Ottawa Citizen revealed that the scandal caused Canadian Heritage to postpone the long-planned unveiling of Ottawa’s controversial “Victims of Communism” monument.

The Maple reported that the unveiling would be delayed back in late October, days before hundreds of dignitaries and monument sponsors were expected to attend the formal event.

At the time, Canadian Heritage spokespeople would only say that the unveiling had been postponed to ensure the monument was compatible with what it regarded as Canadian values.

The Citizen’s report said that planning for the public ceremony came to a halt on October 13, three weeks after Hunka was honoured in Parliament.

Records obtained by the Citizen showed that a Canadian Heritage project manager responsible for the monument was concerned about the possibility of Nazi collaborators being included on the monument’s “wall of remembrance,” a problem which she acknowledged had already been highlighted in the media.

The same documents indicated that Canadian government officials had determined other names listed for remembrance on the monument were SS volunteers or Nazi collaborators. The exact number of problematic commendations was redacted from the documents.

The issue also appears to have attracted the attention of Global Affairs Canada (GAC), which warned their counterparts at Canadian Heritage that an improperly vetted commemorative list could lead to significant controversy in Canada and abroad.

GAC further noted that anti-Communist and anti-Soviet individuals and military units active during the Second World War were often Nazi collaborators and war criminals.

Issues surrounding the monument have raised concerns for several years. In 2021, CBC News reported that virtual commemorative bricks, purchased as part of a fundraising effort for the monument, had been dedicated to a variety of Nazi collaborators, suspected war criminals and Second World War-era fascists.

These included Roman Shukhevych, a Ukrainian ultranationalist believed to have been responsible for the massacres of about 100,000 Poles, as well as thousands of Jews, Russians and Ukrainians in Western Ukraine during the Second World War.

Shukhevych is commemorated with a statue at the Ukrainian Youth Unity Complex in north Edmonton. His statue is protected by a security system paid for by the federal government.

The rationale for the government funding was that the statue, which has been targeted with anti-fascist graffiti, needed to be protected from “hate crimes.”

The “Victims of Communism” monument’s public unveiling has been postponed to an undetermined date in 2024. In keeping with other public monument unveiling ceremonies in Ottawa, a Canadian Heritage spokesperson confirmed to The Maple that the public will not be invited to attend.

Back in 2007, the monument was initially slated to cost an estimated $1.5 million drawn entirely from private donations. It now carries a price tag of $7.5 million, with the additional costs covered by public funds.

More Fallout

The monument’s delay is not the only piece of fallout to have emerged from the Nazi Parliament scandal.

Last month, reports confirmed that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had invited Hunka to attend a rally in Toronto to support Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who was in Canada on an official visit.

The revelation contrasted sharply with statements made in the immediate wake of the scandal, when the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) placed the blame for Hunka’s invite to Parliament entirely on Anthony Rota, who resigned as House Speaker as a result.

The PMO said Hunka was recommended for an invitation to the Toronto rally by the Ukrainian Canadian Congress (UCC).

Critics have accused the organization of representing a section of the diaspora community that has attempted to revise the reputations of Second World War-era Ukrainian collaborators. In 2017, the UCC announced a $25,000 donation to support the creation of the “Victims of Communism” monument.

The organization did not respond to a request for comment from The Maple for this article.

In a 2019 interview with Radio-Canada, historian John-Paul Himka explained that the UCC represents the section of the Ukrainian-Canadian community that was responsible for the creation of the Shukhevych monument in Edmonton.

According to Himka, that section of the Ukrainian-Canadian community has been active in advocating a revisionist perspective of the history of the Shukhevych-led Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) and the faction of the wartime Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists led by Stepan Bandera, who was a far-right Ukrainian ultra-nationalist and Nazi sympathizer.

Shukhevych and Bandera, and the interrelated organizations they led, were Nazi collaborators and are widely viewed as being responsible for some of the most brutal ethnic cleansing campaigns of the war.

A Move To Transparency?

News reports about Trudeau’s knowledge of Hunka’s invitation to Parliament came on the heels of Immigration Minister Marc Miller’s announcement in early February that the government was releasing previously redacted portions of the “Rodal Report.”

The report, prepared by historian Alti Rodal, provided a historical accounting for how suspected war criminals made their way into Canada after the Second World War. Rodal prepared the report as part of the 1986 Deschênes Commission, an investigation into suspected war criminals living in Canada.

However, only about 15 previously redacted pages from the over 600-page long document were actually released last month, and much of the information contained in those pages had already been known for years.

Despite this, Miller claimed his office had made “the vast majority of the Rodal Report publicly available.” The Rodal Report had been listed as “secret” as recently as 1997, but search results from online news archives reveal that at least some of the report’s contents had been available for public scrutiny and widely reported on at least 10 years earlier.

Portions of the report remain redacted despite Miller’s plea that “more can and should be done to provide transparency.” In the press release that accompanied the Rodal Report announcement, Miller was also quoted saying:

“This release is one part of the Government of Canada’s ongoing commitment to transparency, and to reviewing what additional historical records related to the investigation of war crimes can be released. Engagement with affected communities is ongoing, and the government is steadfast in ensuring that Canadians feel safe.”

Despite this apparent commitment to transparency as it pertains to the archival record, the Canadian Press recently reported that the government’s War Crimes Program — which was launched in 1998 to prevent war criminals from finding safe haven in Canada — hasn’t updated the public on its activities in eight years, and has only issued two reports since 2008.

The program’s budget has also remained unchanged. From its launch up until 2008, the program — which included cooperation between the immigration and justice departments, as well as the Canadian Border Services Agency and the RCMP — issued annual reports on its activities and the outcomes of hundreds of investigations into suspected war criminals or people credibly accused of committing crimes against humanity.

The program was launched more than a decade after the Deschênes Commission issued its final report, after an investigative report on the American weekly news program 60 Minutes revived interest in the issue in 1997.

Titled “Canada’s Dark Secret,” the 60 Minutes program reported that the Simon Wiesenthal Centre had supplied an American private investigator with the names of suspected war criminals. The investigator was able to locate hundreds of them living peacefully and openly across Canada.

The same report indicated that Canadian officials had made essentially no effort to find or prosecute any of the suspected war criminals, even in the aftermath of the Deschênes Commission.

Most significantly, historian Irving Abella told journalist Mike Wallace that former prime minister Pierre Trudeau had admitted that Canada didn’t pursue the war criminals issue because he was concerned it would lead to conflict between Eastern European diaspora communities and Canada’s Jewish population.

The recent release of the Rodal Report’s previously redacted sections confirmed what was reported more than a quarter century ago.

The move was the first instance of the Trudeau government purportedly following through on a statement the prime minister made shortly after the Nazi Parliament scandal, in which he said senior bureaucrats were reviewing the Deschênes Commission report with an aim to make more of it public.

The release nonetheless falls far short of what representatives of Canada’s Jewish community, its Eastern European diaspora communities victimized by the Nazis and their collaborators, as well as historians, archivists, and Holocaust scholars have demanded of the Canadian government for nearly 40 years.

The issue is far from settled.

Taylor C. Noakes is an independent journalist and public historian from Montreal.