Whenever you hear an employer making a public fuss about the potential impact of a strike on consumers, take it as an indication that the workers in question have strategic leverage. This was the case in the recent lockout and strike by Teamsters union members at Canadian Pacific (CP) Rail. As of the morning of March 22, a partial agreement had been reached between the parties, with outstanding issues related to wages and pensions to be settled through binding arbitration.

After stonewalling the union at the bargaining table, CP Rail locked out more than 3,000 members of the Teamsters Canada Rail Conference (TCRC) on March 20. The union and company had been at the bargaining table since September negotiating a new collective bargaining agreement to replace the contract that expired on December 31.

In early March, as negotiations dragged on and the company seemed reluctant to address workers’ issues, Teamsters members voted by 96.7 per cent to authorize a strike. As the March 20 strike deadline approached, federal meditators were unable to broker a deal and the two sides remained far apart on issues related to wages, pension contributions, and work rules.

Throughout the last several weeks of negotiations, CP Rail had been calling on the union to accept binding arbitration, whereby both sides would allow an arbitrator from the Canadian Industrial Relations Board to impose an agreement. Arbitration is typically favoured by whichever side feels it has at the upper hand at that stage in the bargaining process. In general, however, unions believe that the best contracts are won at the negotiating table, where the autonomy of workers and their bargaining representatives isn’t curtailed by government-appointed arbitrators. That the Teamsters have now accepted a deal that will move most key issues to arbitration likely has much to do with the mounting threat of back-to-work legislation.

The company’s line in the media was that it chose to force a strike on the union this past Sunday in order to protect the “stability” of the industry by not giving in to wage and pension demands. “The world has never needed Canada’s resources and an efficient transportation system to deliver them more than it does today. Delaying resolution would only make things worse. We take this action with a view to bringing this uncertainty to an end,” CP president and CEO Keith Creel told Freight Waves, an industry publication. The fragility of the COVID-19 recovery, rising inflation and “supply chain shortages” have been excellent cover for the company to deflect from what are serious problems facing rail workers.

However, the issues contributing to this latest Teamsters-CP Rail strike go back much further than this round of bargaining. CP has been engaged in a decades-long project to overhaul its freight operations and impose drastic cuts and work intensification on union members. Between 2012 and 2016, the company cut 4,500 jobs, roughly 23 per cent of the total workforce. This resulted in staffing shortages onboard increasingly longer trains. Not only were workers deeply unhappy about these cuts, safety conditions worsened as workloads and time away from home grew.

Strikes in 2015 and 2018 sought to address some of these issues, but CP refused to rectify underlying problems caused by its “lean production” approach to labour. In February 2019, three Teamster union members were killed on the job when a train derailed, the likely result of poor safety measures. An RCMP criminal investigation against CP is ongoing.

As in many other industries, labour shortages in rail have been artificially created by systematically degrading wages and working conditions to the point where workers are driven out of the industry altogether. Understaffed, “lean” supply chains, promoted by companies as an efficient approach to shipping and international logistics, then buckle under the slightest external pressure. Rather than vague “inflation,” this has been the story of the pandemic recovery. For decades, corporations have placed profit maximization in global logistics above all else. The entirely predictable result is a “supply chain” unable to cope with pandemic disruption.

On the other hand, fragile supply chains also increase labour’s potential to disrupt business as usual by highlighting points of strategic vulnerability. When profit increasingly depends on outsourcing raw material supplies and manufacturing capacity, the infrastructure necessary to move goods become key choke points for labour. Companies know this and want the heavy hand of the state to protect them from the consequences of their years of attacks on wages and working conditions, i.e. from defensive strikes.

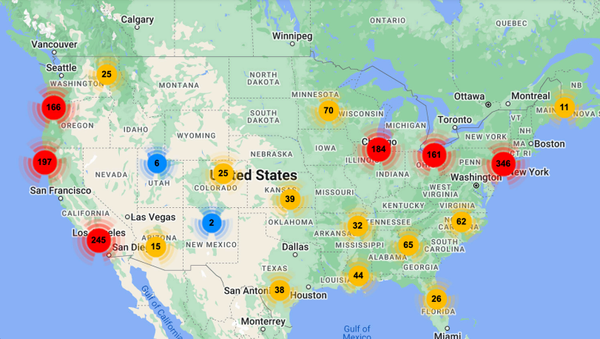

The above process was on full display this past week. As the strike deadline approached, CP’s message in the media relied on framing the union’s positions as unreasonable and placing the COVID-19 recovery in jeopardy. After months of discussion about the fragility of “the supply chain” — a term almost completely detached from the workers that make it operate — the company was able to position rail transport as “essential” and put pressure on the federal government to potentially intervene if a work stoppage dragged on. In early March, CP said: “A work stoppage of any duration at CP will impact virtually all commodities within the Canadian supply chain, thereby crippling the performance of Canada’s trade-dependent economy. The consequences of a work stoppage will be felt long after workers return to work and service resumes. This is an issue of doing what is best for Canada’s economy.”

Although Liberal Minister of Labour, Seamus O’Regan, publicly encouraged the two sides to return to the bargaining table, pressure was clearly mounting for the government to introduce back-to-work legislation against the Teamsters. The Premier of Saskatchewan, Scott Moe, went so far as to call on the federal government to declare rail an “essential service” and permanently prohibit union members from striking.

Business lobby groups, such as the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, were calling for immediate back-to-work legislation. The Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters, as well, wanted strike-breaking legislation. According to the CBC, “Fertilizer Canada, a group representing manufacturers, wholesale and retail distributors, also called on the federal government to take immediate action.” Roughly 75 per cent of fertilizer is moved by rail in Canada. The Canadian Cattlemen’s Association and the National Cattle Feeders’ Association were both demanding repressive government action against the union. Other business representatives were equally concerned about the potential impact on food prices, as well as the costs of other raw materials, such as wood and grain.

Despite widespread acknowledgement that price inflation isn’t being driven by wage pressure, there was virtually no appetite for the notion that Teamsters might have a constitutionally-protected right to bargain freely over wage and pension increases. Instead, the business lobby recognized that the Teamsters were in a strategically advantageous position and went to work creating a media frenzy about the strike’s impact on consumers, hoping the government would rescue them with repressive back-to-work legislation.

In all the coverage I read about the CP work stoppage, not a single piece mentioned that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms ostensibly protects union members’ rights to collectively bargain and to strike, free from government interference. No mention was made either that the use of back-to-work legislation disincentivizes employers from bargaining in good faith.

Since 2009, back-to-work legislation has been introduced or threatened to end at least three separate rail strikes. The rail companies have learned the lesson: they can exploit labour and worry little about the consequences when the government is willing to step in and bail them out. Although striking-breaking legislation wasn’t deployed this time around, its threat undoubtedly shaped the short duration of the strike and likely changed the Teamsters’ calculation concerning what victories were possible from the picket lines.

For the sake of TCRC members at CP, let’s hope federal arbitration is favourable. Nevertheless, the plague of back-to-work legislation, and the climate of fear it generates, must be addressed sooner or later by the entire labour movement.

Member discussion