In October, Indigo won an order blocking a website calling for a boycott of the bookseller. The case, largely ignored by the media, revealed a new and unlikely front in the struggle in Canada between the movement for Palestinian liberation and Israel’s powerful supporters, one which could have ramifications for other solidarity efforts.

In August, anonymous activists created the website IndigoKillsKids.ca, which has been endorsed by the Canadian BDS Coalition and other pro-Palestine organizations. The site, borrowing Indigo’s visual style, told visitors to boycott the company, promoted the September 25 day of action against it and offered links to various BDS resources. It was the latest phase in a years-long campaign to boycott the bookseller over the HESEG Foundation — founded and run by Indigo CEO Heather Reisman and her husband, Indigo’s owner Gerald Schwartz — which offers scholarships to Israeli army veterans without family in Israel.

Soon after the site went live, Indigo’s lawyer demanded it be taken down, and two weeks later filed a suit requesting an order for all major internet providers in Canada to block the site. The court granted the request, first under an interim decision issued September 19, and then with a two-year injunction on October 23, effectively shutting down the offending website along with several social media accounts for the foreseeable future. That month, it was reported that Israel’s military had killed at least 16,900 children in its assault on Gaza.

The legal issue in the case had little to do with Indigo’s alleged support for Israel’s genocide. Rather, the proceedings centered on the website’s biting appropriation of the branding associated with the division Indigo Kids, darkly parodying the cute, non-threatening logo with a horrifying assertion: “Indigo kills kids.”

Legally, the trouble was that Indigo claimed ownership over both the logo and the phrase it contained through copyright, which gives creators control over their artistic works, and trademark, which protects companies’ ability to be identified with their products.

In answer to Indigo’s motion, the owners of the website had several arguments available to them. Under copyright law, the creator of an image, or whoever they sell the rights to, has the largely exclusive right to reproduce it. But the public also has rights, including the right to reproduce protected works under certain circumstances, called “fair dealing” in Canada. As the courts tell us, the public’s fair dealing rights are integral to the copyright regime and should not be treated as narrow loopholes. Parody is a form of fair dealing, defined by the court to include “the evocation of an existing work while exhibiting noticeable differences and the expression of mockery or humour.”

Based on the parody exception, the court could have ruled that the words and images on the website, mocking Indigo’s child-friendly branding while its founder materially supports veterans of a military that has killed thousands of children, were entirely within the rights of those who made it.

As for trademark, the courts have ruled that use of a registered mark outside of the sale or transfer of goods — such as on a website with no books to sell — doesn’t engage the Trademark Act. Indigo’s allegation of a trademark violation in addition to copyright, then, seems problematic.

Then, of course, there is freedom of expression, enshrined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and clearly impacted when the state intervenes to silence activists. Surely, this principle should at the very least have been part of the court’s analysis.

But despite these very real issues for Indigo’s case, the company got its order. The words “fair dealing” and “parody” are found nowhere in the decision, while freedom of expression is mentioned only in passing.

The court’s failure to address these possible defences was a likely consequence of the way the case was argued — or more precisely, wasn’t. The site’s anonymous creators didn’t appear in court or send a lawyer to represent them, perhaps fearing legal repercussions for announcing themselves as the John Does named in the lawsuit or because they lacked the financial resources needed to mount a defence, particularly on such short notice.

It’s a familiar story for movement politics in court: grassroots activists challenging the destructive power of capital and coming up against a legal system that privileges property rights, whether physical or intellectual, over organized political expression. So it was with the pro-Palestine encampments thrown off university lawns this summer. In copyright, too, examples abound: the striking Michelin workers enjoined from using the Michelin Man on their leaflets in 1996, or the filmmaker blocked by Warner Bros. Discovery from screening The People’s Joker, an independent film exploring a trans woman’s search for identity.

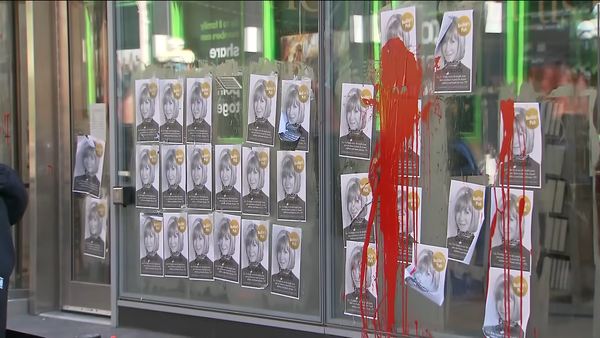

Familiar, too, was Indigo’s use of the law, and its deep pockets, to fight the advocates for the boycott. Last November, after at least one personal call from Reisman to Toronto’s chief of police, 11 people were arrested for allegedly postering an Indigo store in the city. Some of these arrests were in violent and chaotic middle-of-the-night raids, which a policing expert told The Breach are typically reserved for “gun or drug” busts. Several of the charges then laid have since been dropped, though others remain before the courts. The “Indigo 11” story sparked a flurry of reactionary denunciations, and, in some places, a more open and serious discussion about Indigo, HESEG, and the boycott in the mainstream press.

Not so for Indigo’s copyright battle, which garnered precious little attention in the media. The difference in coverage between the two Indigo cases may be a predictable result of the relative dryness of intellectual property law compared to the alleged criminality, however minor, that drew the media to the store’s poster-stricken window. If you want to break a law to get eyes on your cause, these examples suggest, don’t make it the Copyright Act.

But despite the different media responses, both Indigo cases carry the same danger for the movement, threatening to chill Palestine advocacy by stoking fear of state repression. This kind of fear, together with that of doxxing, employer reprisal and even physical violence, are perhaps the greatest threat to the efforts of the Palestine movement in Canada.

Unfortunately, these dangers have no easy answer except for organizers to learn about the various laws that might impact them — including copyright, criminal, defamation and employment — and strategize accordingly. That, and to keep organized and motivated to continue fighting Israel’s genocide. If the law is a weapon of suppression, solidarity backed by knowledge and strategy are the tools we have to resist.

After all, this cautionary note should not be overstated. The site-blocking order may have killed Indigokillskids.ca and set back its creators, but it didn’t stop them. Within 48 hours of the interim order, the blocked site re-emerged with the URL boycottindigobooks.com, stripped of the offending designs but still calling for a boycott and retaining the rest of the original site’s content.

With the ongoing holiday season, the push to boycott Indigo and other Israel-aligned retailers is sure to ramp up. Boycottindigobooks.com remains online and, so far, hasn’t faced additional legal action. On this front, as on the others, the struggle for Palestinian liberation continues.