Migrant farm workers in Ontario are once again calling on the provincial government to enact lifesaving heat protection standards.

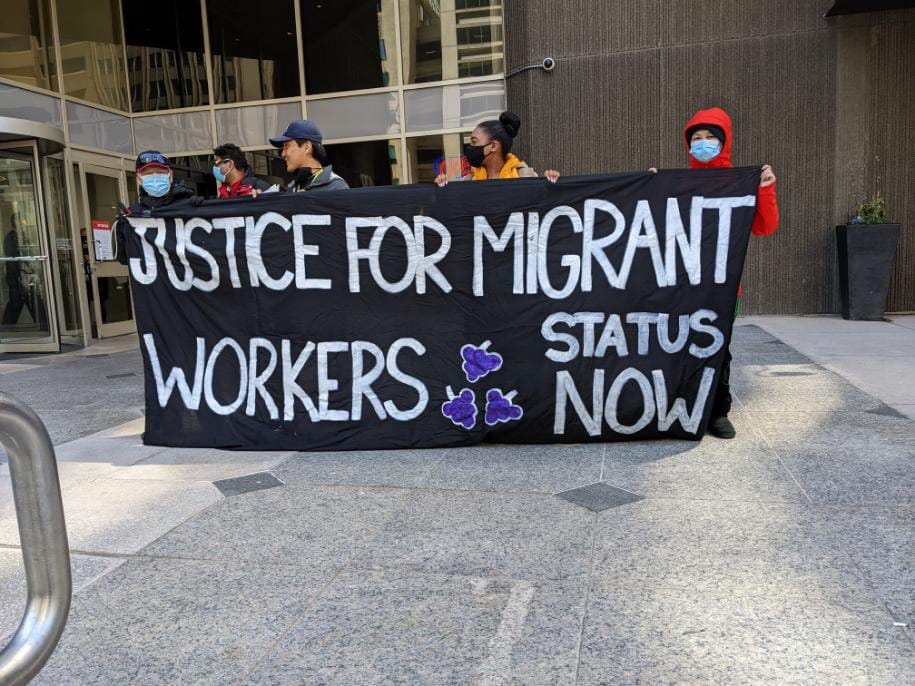

On July 8, Justice for Migrant Workers (J4MW) released an open letter addressed to Ontario Premier Doug Ford and Minister of Labour David Piccini urging them to implement emergency regulations aimed at protecting migrant agricultural workers from extreme heat.

As present, no specific occupational health and safety laws in Ontario regulate heat exposure among migrant farm workers.

J4MW is a volunteer organization made up of current and former workers, activists, and scholars “who advocate for fairness, dignity and respect for agricultural workers.”

As J4MW writes, “2024 is once again becoming one of the hottest years on record. In the last few weeks alone, temperatures have soared and Ontario has become a heat dome while tens of thousands of workers labour without heat protections.”

On June 20, the migrant workers’ organization issued a similar call for action, as it had done the previous year. To the latter call, the government of Ontario responded with a plan to implement a heat regulation to protect all workers. The proposed requirement would introduce heat-stress exposure limits and compel employers to implement measures to control heat exposure as well as train workers on how to recognize the issue and protect themselves.

However, since this proposal was outlined last year nothing has materialized. As J4MW sees it, the government “twiddles its thumbs [while] farm workers continue to work under the same backbreaking conditions as always.”

Even if such a heat exposure framework had come to pass, it’s unclear to what degree the plan would have addressed the unique experiences of migrant farm workers. The proposed regulation would have to be applied “to all workplaces to which the OHSA [Occupational Health and Safety Act] applies,” according to the Ministry of Labour, and although the OHSA applies to farms, there are also special rules to consider. Moreover, such a general framework is not the same as an industry-specific regulation, for which J4MW is calling.

At present, the government claims that employers have a general responsibility to protect workers from heat stress, but without the industry-specific standard such a duty is nearly impossible to enforce in agriculture. Moreover, although current legislation establishes a general duty to protect — and encourages employers to adopt programs to prevent heat stress and heat-related illnesses — it depends heavily on the willingness of employers to provide such protections to workers. Establishing stronger, industry-based regulations and ramping up enforcement would take the onus off of vulnerable workers to assert their rights.

According to research cited by J4MW, farm workers are 35 times more likely to die from heat exposure than the general public.

A range of factors structure the risks experienced by migrant farm workers. Clearly, the environmental risk of working outdoors as climate change drives average temperatures higher is a major issue. But it is also the conditions of farm work that can render climate risk fatal. Because migrant workers in agriculture are exempted from many labour and employment regulations, they are often denied basic legal protections. Various special rules govern the law of agricultural work in Ontario depending on the type of farming being done. Generally, migrant agricultural workers are not entitled to specified breaks or rest periods, overtime pay, or inclusion under hours of work limitations. Overwork thus ends up being a significant factor contributing to heat stress.

Where migrants work on a piece-rate system, overwork can further exacerbate heat exposure because longer hours of work may be necessary to earn adequate wages.

Additionally, exercising what limited rights migrant workers have can be difficult under circumstances where employers maintain outsized control over workers’ lives. Most migrant farm workers come to Canada through one of several temporary work programs that tie them to their employers. Workers are unable to leave their job and seek employment elsewhere if they experience abuse or have their rights violated. They are also dependent on their employers for housing and other amenities. Dependent circumstances such as these are generative of exploitation.

It was not for nothing that a United Nations official referred to Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program as “a breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery” after finding workers labouring in what he described as appalling conditions in a report last fall.

Fear of retaliation commonly militates against workers in low wage industries filing complaints against their employers. But such fears are magnified considerably for migrants, whose status in the country is precarious and whose employers can terminate their residency along with their employment.

It is for these reasons that J4MW, like many migrant rights organizations, advocates for permanent residency status for workers upon arrival. Ending temporary status would not only limit employers’ ability to violate workers’ labour and employment rights but would also provide workers with equal access to vital services and income support programs, such as public health insurance, Employment Insurance, the Canadian Pension Plan, and workers’ compensation. Despite recent promises to “revamp” workers’ compensation after the program decided to pay out millions to wronged migrant workers injured on the job, the announced reforms will still exclude the thousands of workers who arrive in Canada through the agricultural stream of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.

As J4MW points out, the Ontario Human Rights Commission has recognized access to cooling as a human rights issue and noted the racial disparities in exposure to heat-related risks. Such an acknowledgement thus has strong implications for migrant workers. As J4MW writes, “Denying migrant farmworkers, who are overwhelmingly racialized, who are more likely to be injured on the job, and who work long hours for little pay, is a form of environmental racism.”

Among the measures J4MW would like to see implemented are heat stress protections and clear temperature and humidity triggers; paid breaks and permanent paid sick days; holiday pay; employer-provided shelter, washrooms, and water; first-aid, hydration, and on-site medical support; anti-reprisal protections; the ability to submit third party complaints to the Ontario Labour Relations Board; ending migrant farm workers’ Employment Standards Act exclusions; and extending Occupational Health and Safety Act protections to cover migrant workers’ accommodations.

Several American jurisdictions, such as Washington, California, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Colorado, have enacted regulations similar to what J4MW is advocating, J4MW claims. As well, British Columbia has relatively strong heat exposure protections within its Occupational Health and Safety Regulation. (Migrant farm workers in B.C. can also unionize more easily, a right some are beginning to exercise.) These could easily be built upon to protect farm workers in Ontario. Moreover, the Ontario Federation of Labour has proposed a series of occupational health and safety amendments that would better protect workers from extreme heat.

That migrant workers still have to fight for these basic rights in Canada’s largest and most prosperous province is simply an indication of the injustice upon which our food system is currently built.

As a bare minimum, migrant farm workers deserve robust protections from heat stress, poor air quality and chemical and pesticide exposure. Making such rights meaningful in practice also necessitates strong anti-reprisal rules to ensure that employers cannot retaliate against workers for speaking up and exercising their rights to a safe workplace.

Recent Class Struggle Issues

- July 15 | LCBO Workers Strike To Combat Doug Ford’s Privatization Plans

- July 8 | WestJet Mechanics’ Union Soars To A Major Victory For Labour

- July 1 | Declining Self-Employment Rates Are A Good Sign For Workers

- June 24 | Unions Resisting Coordinated Push For Return To Offices