On February 24, Russia invaded Ukraine. Immediately after the invasion began, the phrase ‘stand with Ukraine’ started trending in Canada, and it has remained pervasive ever since. Profile photos, statuses, newspapers, homes, businesses, government buildings, landmarks, cars, websites — everywhere we go, we’re faced with a demand to “stand” with a country being invaded. That sounds reasonable and even commendable in theory, but what has it meant in practice?

Some manifestations of this sentiment have been applaudable, such as ones seeking to provide medical aid and resources to Ukrainians and help to ease the resettling process for internally displaced people and refugees. There’s little reason for me to doubt that the majority of people contributing to these campaigns have meant well, doing what they can to help those they feel sympathy for (although, of course, the fact that Canadians seem to be so much more willing to help Ukrainians than other groups hints at underlying issues with racism).

However, from the beginning, “standing with Ukraine” has meant something very different for Canada’s leadership and its allies, the right-wing nationalist elements of the Ukrainian diaspora here and Volodymyr Zelensky’s government as well. For these forces, standing with Ukraine carries a whole other set of conditions and expectations, which have come to define the acceptable parameters of debate within Canada. These expectations are enforced by politicians from all parties, media and corporations, and violating them, despite how genuinely you may care for the Ukrainian people, results in consequences.

These expectations aren’t reasonable or commendable, however — they’re dangerous. And if following along with these conditions is what it takes to “stand with Ukraine,” then I won’t, and neither should you.

So, what are these expectations? What has standing with Ukraine meant supporting in practice?

To start, “standing with Ukraine” has meant being expected to believe myths about the country and its leader. For example, on March 9, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau claimed that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is an attack on “the values that form the pillars of all democracies,” and that Zelensky is “defending the democratic values that are so important to all of us.”

Dimitri Lascaris — lawyer, writer and former candidate for the federal Green Party — offered a more accurate view of the country in his July article “Ukraine’s ‘Servant Of The People’ Is A Western Fiction.”

Lascaris writes, “Under Zelensky, Ukraine’s government has aggressively suppressed free speech and political pluralism. In early 2021, Zelensky signed a decree banning three ‘pro-Russian’ television channels. […] The Ukrainian Union of Journalists reacted harshly to Zelensky’s ban, stating ‘the deprivation of access to Ukrainian media for an audience of millions without a court … is an attack on freedom of expression.’ […] Ukraine’s ‘lion of democracy’ banned OP-FL in March of this year, along with ten other ‘pro-Russian’ and left-wing parties […] Zelensky’s government also arrested two youth communist leaders and accused them of conspiring to overthrow the government. Following their arrest, the World Federation of Democratic Youth, a U.N.-recognized global alliance of progressive youth organizations, stated ‘After being persecuted, repressed, kidnapped, and tortured by the…Ukrainian Security Service, now their right to defense from the accusations [against them] is being violated.’ None of the eleven parties banned by Zelensky is a far-right party. Evidently, Zelensky doesn’t regard Neo-Nazis as a threat to Ukrainian democracy.”

Ukraine isn’t the country politicians have portrayed it as to help craft a narrative of the war as an existential conflict between authoritarianism and democracy. (To be absolutely clear, though, the nature of Ukraine’s leadership doesn’t at all justify the killing of its civilians or the invasion, and Russia is plagued with these problems as well, as Western media reports constantly point out.)

But if the war in Ukraine wasn’t caused by one side seeking to usurp democracy and the other aiming to defend it, why did it start? “Standing with Ukraine” has also meant being expected to not critically examine what happened in the lead up to Russia’s invasion.

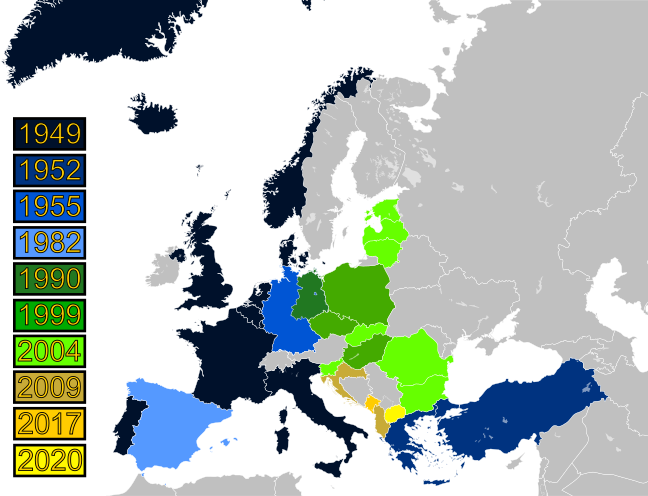

For example, in 1990 a promise was made to Soviet Leader Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO wouldn’t expand “one inch” eastward from Germany. This was followed up by NATO doing just that, adding 14 countries beyond the border they promised to stop at. In 2008, NATO issued a declaration stating that they welcomed Ukraine and Georgia joining NATO as well, and pledging that one day they’d gain membership, bringing the military alliance right to a greater portion of Russia’s border. In 2014, some Western countries backed a coup against Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, just months after he made a trade deal with Russia instead of the European Union. And since then, Ukraine (with Western-backing) has repeatedly violated the Minsk agreements, intended to end the conflict in the Donbas that erupted after the coup. All of these facts have concerned scholars for decades, who warned that if NATO didn’t stop, war would eventually break out.

Instead of considering this history, “standing with Ukraine” has meant swallowing a narrative where Russian President Vladimir Putin is a deranged, bloodthirsty lunatic with no reason for what he does (regardless of whether those reasons justify his actions).

“Standing with Ukraine” has also meant being expected to ignore, minimize or even celebrate neo-Nazi factions of the country’s armed forces, which were openly embraced by the government well before the invasion began.

As I wrote in January, “In May 2014, amidst the unrest in Ukraine, the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion was formed as a civilian paramilitary group to combat Russian separatists. The organization has never been shy about its Nazi links and ideology. […] In November 2014, the Battalion was officially incorporated into the Ukrainian National Guard. This means the Ukrainian government knowingly decided to make a neo-Nazi group part of its forces, giving, at the very least, a tacit acceptance of their ideology.” The Canadian government and military officials, meanwhile, have since met directly with Azov, given them training and taken photos with them that were used in online neo-Nazi propaganda.

From 2014 until a couple months after Russia’s invasion, Canadian media outlets used descriptors of the group that were accurate, including “Ukrainian fascist group” and “ultra-nationalist white supremacist paramilitary regiment.” Starting in May, however, as Azov became more important in the military effort against Russia, the media began whitewashing the group, portraying its far-right ideology as a thing of the past. This was because being honest about Azov was becoming increasingly dangerous for the stability of the “stand with Ukraine” narrative. One particularly noxious example was an August 5 profile from The Globe and Mail of an Azov commander’s wife, which effectively amounted to neo-Nazi propaganda, allowing her fawning depictions of the group as “real heroes” to go unchallenged.

This rehabilitation of Azov and other neo-Nazis is so critical because it helps make the next step of “standing with Ukraine” more digestible: supporting military aid for the armed forces they belong to.

Canada’s government notes that it has contributed more than $600 million in military assistance to Ukraine since February, with a $47 million package being sent in October. Today, they announced $500 million more in military assistance, bringing the total to more than $1 billion. They also boast of “assisting with the delivery of aid within Europe” and transporting “4 million pounds of military donations on behalf of our Allies and partners.” Since September 2015, meanwhile, the government claims to have “trained over 33,000 Ukrainian military and security personnel in battlefield tactics and advanced military skills” in order “to prepare Ukraine for this fight,” indicating that the war was a potential goal all along.

Despite this, those “standing with Ukraine” — citizens and politicians alike — are expected to have no reservations about the seemingly-endless flow of military supplies, or else they can be accused of secretly harbouring sympathies for Russia. This is the absolutely essential requirement of those “standing with Ukraine” — and the most dangerous.

But, we’re told that no matter how dangerous this may be, it’s what Ukrainians are asking for, so we need to give it to them (as if that’s a position Canada ever takes when it comes to Global South forces seeking aid to combat their oppressors). Of course, the government really doesn’t want us looking too closely at which Ukrainians are asking for this, and what their histories may be. Instead, “standing with Ukraine” has meant pretending Ukrainians all think alike and want the same things.

For example, we rarely if ever hear from Ukrainians who are anti-war, opposing Russia’s invasion but also preferring a negotiated settlement to never-ending conflict. In March, The Maple’s managing editor, Alex Cosh, spoke to one such person, Yurii Sheliazhenko: “Sheliazhenko, who was regularly awoken at night by the sound of exploding shells, explained that although [Putin] had no right to invade, Canada and other NATO countries had contributed to escalating the conflict by expanding the West’s military presence in Eastern Europe and flooding Ukraine with weapons. In doing so, Canada helped transform Ukraine into a battlefield in a NATO proxy war against Russia, while also refusing to push for a peace deal. ‘Ukraine is encouraged to fight for the last drop of blood,’ Sheliazhenko explained.”

We also certainly never hear from certain Ukrainians in the eastern provinces that have since been illegally annexed by Russia, many of whom had lived in a war zone since 2014 and actually support independence from Ukraine in one form or another. Sure, such sentiment is nowhere near as pervasive as the annexation referendums conducted in September made it out to be, but it does exist, and has historically played an important role in politics within Ukraine.

Those “standing with Ukraine” are also expected to pretend that many of the Ukrainians who are platformed here are actually representative of the entire community, and abstain from investigating their particular ideological backgrounds.

For example, one group mentioned constantly in the media is the Ukrainian Canadian Congress (UCC), which claims to represent the “Ukrainian Canadian community before the people and Government of Canada.” The UCC has been mentioned on more than 1,300 occasions in Canadian media this year alone, according to the Canadian Newsstream database. It also enjoys widespread political support, with the group claiming their meeting last month was attended by: Trudeau, Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland, Minister of National Defence Anita Anand, Minister of International Development Harjit Sajjan, an MP on behalf of Conservative Party Leader Pierre Poilievre, Premier of Manitoba Heather Stefanson and others.

The UCC, however, is on the radical end of war-accelerators in this conflict, having repeatedly called for the imposition of a no-fly zone over Ukraine, which if attempted would likely lead to a nuclear conflict. The group is also funding the fascist-whitewashing “Memorial to the Victims of Communism.” A former leader of the group, according to a 2012 journal article, “paid tribute to the veterans of the Waffen-SS Galizien, and remembered its fallen ‘who perished fighting for the freedom of their ancestral Ukrainian homeland.’” The group also claimed that the president of that veterans’ group “will be remembered as a hero of Ukraine who fought for her independence.” The group has repeatedly denied that Ukrainian Nazi collaborators were such, portraying them as commendable figures that have been targeted with Russian disinformation.

On that note, Freeland, the most prominent Ukrainian in Canada, is also a radical nationalist. Freeland’s grandfather was a Nazi collaborator who worked to produce virulently antisemitic propaganda that justified the mass slaughter of Polish and Russian people during the Second World War. He worked at a paper confiscated by the Nazis from its Jewish owner who would eventually be killed in a death camp, and lived in an apartment taken in the same way from another Jewish family that would meet the same fate. Freeland knew about this history for years, but rather than distance herself from her grandfather, she has said he had a “very big effect” on her, that he “worked hard to return freedom and democracy to Ukraine” and that she is “proud to honour [his] memory.” Freeland also is an ardent supporter of the Holocaust-minimizing Black Ribbon Day, has used Ukrainian fascist slogans and happily posed with a symbol from one of these groups at a pro-Ukraine protest in February.

These are the sorts of people those who “stand with Ukraine” are expected to listen to and support, as if they’re the only ones around, and as if they genuinely represent the best interests of Ukrainians rather than their own twisted ideologies.

Of course, this is part of a long-running trend in Canada, whereby, as Moss Robeson wrote in Passage back in August 2020, “During the Cold War, western governments looked the other way as far-right post-Second World War émigrés from western Ukraine […] began to take control of much of the organized Ukrainian diaspora. This was perhaps especially the case in Canada, where the [Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists’] presence predated the war, and Ukrainians once comprised much of the Canadian Communist Party’s membership. Canada banned the Communist Party and the pro-Soviet Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association in 1940, and months later the government sponsored the creation of what was later renamed the [UCC]. A now-defunct pro-Nazi monarchist group and the OUN-affiliated Ukrainian National Federation were among the founding member organizations of the UCC, which has always enjoyed Ottawa’s recognition as the spokesbody of Ukrainian Canadians.”

And this is perhaps the most galling and dangerous expectation of those who “stand with Ukraine”: having to pretend that never ending and always-expanding war will actually benefit Ukrainians, who are having their country destroyed the longer the war drags on.

Are Ukrainians in a better position now than before their government started publicly seeking to join NATO? Has Ukraine held on to more land than it would have had it merely accepted neutrality between Russia and NATO? Will Ukraine have to give up less in a potential peace agreement now than it would have before the war started, or even within its first month? Will all of those who left Ukraine have more to come back to than they would have before war escalated, if they come back at all? Will Ukraine be in a better position to rebuild post-war now than if things hadn’t escalated?

Where does it end? How much land will Russia need to take before an agreement is reached? How many Ukrainians will need to die?

If Russia happens to be pushed back, how far back will be considered enough? Will it be their borders just before the invasion? Maybe the capturing of Crimea?

If Russia is supposedly performing so poorly that its defeat is just around the corner, how can we believe the claim that a peace deal here isn’t acceptable because it will encourage Putin to attack other countries?

How are we supposed to believe the idea that Putin is a lunatic who will do anything to stay in power, but that he won’t use nuclear weapons if he feels like things aren’t going his way?

If Russia and Ukraine destroy each other, who benefits? Is it the people, or the weapons manufacturers and Western governments who see Ukrainians as convenient and disposable pawns to be used to weaken an opponent without having to do so directly?

Why should we ignore that we’re rapidly moving closer to nuclear conflict — closer than at any point in history since the Cuban Missile Crisis — with a complete lack of the sort of dialogue and diplomacy that existed during past periods of tension? In fact, as outlined in a valuable thread from Jacobin writer Branko Marcetic, “today’s liberal establishment [has] adopted nearly word for word the rhetoric of Cold War hawks who would’ve killed us all.”

The questions go on, and they’re not ones those who call on us to “stand with Ukraine” enjoy addressing or answering. Even asking these questions is enough to get you smeared and shut out of corporate media. Still, they’re questions that must be posed, clearly, loudly and repeatedly.

The ideological fanatics pushing for endless war in Ukraine have had control of the narrative for far too long, spreading propaganda aimed at preventing the public from getting a better understanding of the forces at war, why it started and who it benefits. All they have brought us is more death, crashing markets, starving and freezing populations throughout Europe, and many steps closer to nuclear catastrophe.

Enough.

UPDATE: This article was updated to include an announcement made shortly after it was published that Canada will be sending $500 million more in military aid to Ukraine.