On October 24, former Conservative MP and cabinet member Chris Alexander baselessly accused Ottawa Citizen journalist David Pugliese of being a Russian agent. The remarks came during Alexander’s appearance before a Public Safety and National Security committee meeting, granting him parliamentary privilege and absolute protection from being sued for defamation.

Alexander’s accusation focused on Pugliese’s important reporting on national defence and Ukrainian Nazis in Canada. He claimed that Pugliese’s work often contains themes that “Moscow would be delighted to promote” and “weaken Canadian support for Ukraine.”

I’m a Ukrainian Canadian, and I disagree with Alexander’s remarks.

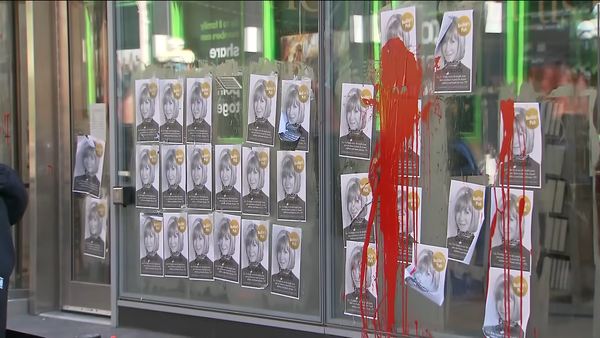

Pugliese’s reporting has been vital in exposing the fascist underpinnings of some Ukrainian organizations in Canada, as well as how the Canadian government welcomed Nazis after the Second World War. In order to deal with Nazis and Nazi sympathizers in the Ukrainian Canadian community, we need to first acknowledge that they exist. Without Pugliese’s work — as well as reporting by The Maple, The Breach and independent journalists such as Moss Robeson — far fewer Canadians would be aware of this blight on the country.

Alexander characterizing Pugliese’s reporting as advancing Russian propaganda is an attempt to divert attention away from the real issue, and is reminiscent of McCarthyism. Moreover, while Alexander frames his accusations as being in solidarity with Ukrainians, he actually ignores or outright denies the existence of Ukrainian Canadians like me who want our community’s Nazi problem to be known to the public.

It wasn’t always this way in the community, as the Ukrainian diaspora in Canada has a rich socialist and anti-fascist history.

The vast majority of the first two waves of Ukrainian immigrants to Canada in the late 19th and early 20th centuries consisted of poor farmers and labourers. Many of these immigrants were deeply involved in early left-wing movements in Canada. They also formed their own socialist organizations, such as the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party of Canada, and the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association, which played an important role in the General Strike of 1919.

In an attempt to crush the established Ukrainian left, Canada allowed Ukrainian nationalists to be ratlined into Canada after the end of the Second World War. These Ukrainians brought their fascist and anti-communist beliefs with them, setting up their own ultra-nationalist community organizations and attacking others. In 1950, for example, a Ukrainian Labour Temple in Toronto was bombed. The national secretary of the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians blamed it on members of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS, often called the Galicia Division, a voluntary unit in which volunteers swore an oath to Adolf Hitler

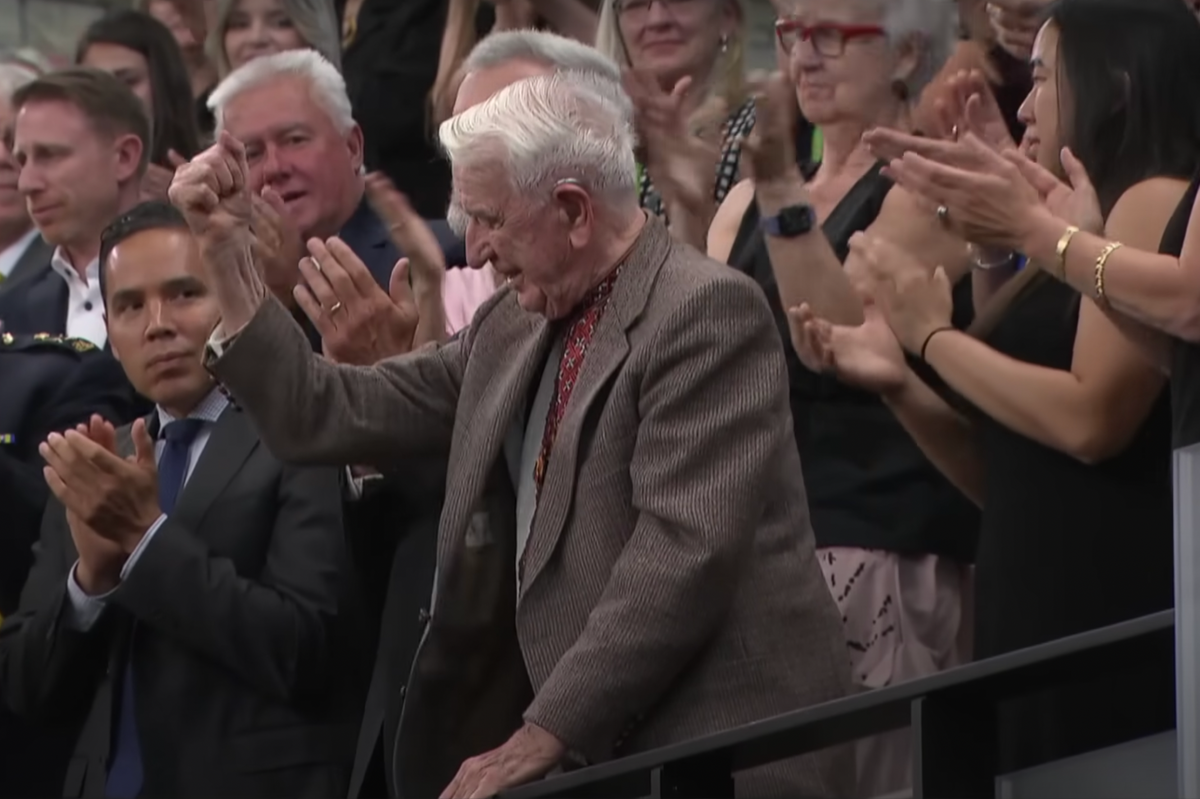

Yaroslav Hunka is now perhaps the most well-known example of a Ukrainian who came to Canada during this period due to the scandal that emerged after he was given a standing ovation before Parliament last year. Hunka made his way to Canada in 1954 after serving in the Galicia Division.

But Hunka was not alone. University of Ottawa history professor Jan Grabowski told the CBC that Canada welcomed members of the Galicia Division knowing who they were and what they did. The government was willing to overlook their associations because “anti-communists were prized above everything else,” said Grabowski.

As Pugliese reported in September, Library and Archives Canada is currently being pressured to release a list it possesses of 900 alleged Nazi war criminals who fled to Canada, with some among them certain to be Ukrainians.

One of the groups calling for the list to be released is the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians. Unfortunately, other Ukrainian Canadian groups have opposed the move. This shouldn’t come as a surprise given that the organizations established by some of the post-Second World War Ukrainian immigrants now play a major role in the community, and have kept up the fascist-worship.

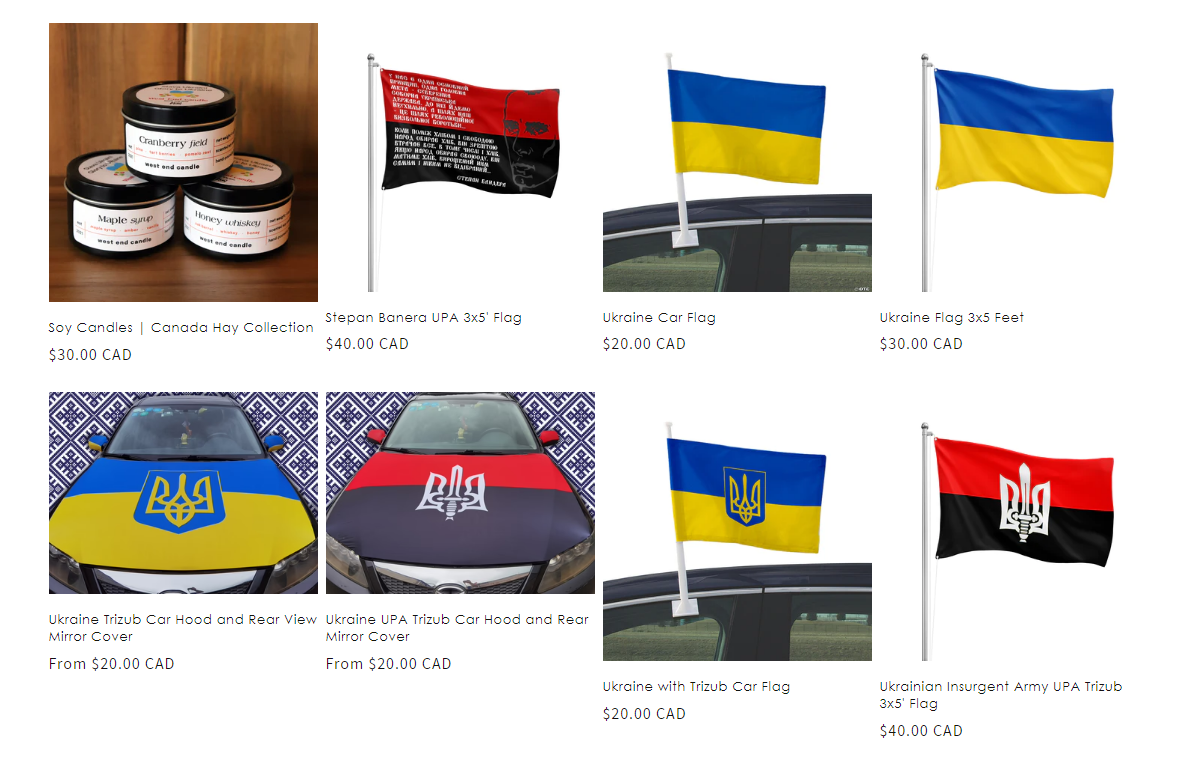

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the paramilitary wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, was led by Stepan Bandera, and later Roman Shukhevych, two Nazi collaborators. They continue to be celebrated by some Ukrainian groups in Canada, with, for example, a bust of Shukhevych outside the Ukrainian Youth Unity Complex in Edmonton and portraits of Bandera in Ukrainian community centres. The characterization of fascists as “victims of communism” has also become mainstream.

But the community is not a monolith, and Pugliese’s reporting has been a service to those of us who oppose fascism. In fact, we need more journalists to call attention to the specific organizations and people in our community with ties to Ukrainian ultra-nationalism so we don’t get lumped in with them.

A day after Alexander’s testimony, Canada’s National Observer columnist Max Fawcett wrote that if a story “advances a foreign government’s narrative,” journalists should “tread more carefully,” and specified that he’d never write “a column that advances a Russian narrative.” This sentiment is dangerous, as it places more importance on whose “narrative” one is supposedly advancing than telling the truth.

In this case, the truth is an important story of interest to many Canadians, including Holocaust survivors and their descendants, as well as Ukrainian Canadians like me. Pugliese and journalists like him aren’t foreign agents or acting with a nefarious agenda — they’re aiding the Canadian public.