Jan Reynolds, who lives in Guelph, Ontario, wasn’t feeling well recently. Her friend came over to check up on her, and was surprised when she opened Reynolds’ refrigerator.

“How come your fridge has only got a jug of water with cucumber slices in it, and a little bit of lettuce?,” Reynolds recalled her friend asking as she looked at the fridge’s sparse contents.

Reynolds explained that she hadn’t been able to go out and buy groceries, as supermarket costs have become nearly impossible for her to afford. Her friend offered to buy some food, but Reynolds was concerned that she didn’t have enough money to pay her back.

Reynolds moved to Guelph just as the COVID-19 pandemic hit more than two years ago. Last July, a report published by Rentals.ca found that the city had the seventh most expensive rents for one-bedroom apartments in Canada.

Grappling with rising costs, Reynolds, who turned 70 this year, relies on Old Age Security (OAS) payments to survive. In July, OAS payments are set to increase by 10 per cent for those over 75, meaning Reynolds will not benefit.

“It's a struggle to make ends meet,” Reynolds told The Maple. She said she has found it difficult to find part-time work to supplement her income because of her age, and because of the pandemic. She has no family who can provide support.

Reynolds is vegan, but said the rising cost of food at grocery stores means that her veganism is no longer by choice. “I can't afford to go buy eggs; I can't afford to go buy cheese; I can't afford to go buy bread,” she explained. “I have $30 a week to spend on food.”

According to the most recent Consumer Price Index (CPI) update, Canadians paid 9.7 per cent more for food purchased from grocery stores in April than they did during the same month last year. Some basic items increased by an even higher rate, with shoppers paying 12.2 per cent more for bread than they did last year.

Prices for fresh vegetables, a core part of Reynolds’ diet, increased by 8.2 per cent. These rising costs mean she is among the nearly one-in-four Canadians who are not eating properly because they don’t have enough money to buy healthy food.

OAS, along with other federal benefits, are indexed to increase at the rate of inflation. Still, meeting basic costs was tough even before soaring inflation hit.

“I get tired, because I know I'm not, at times, getting enough nutrients,” Reynolds explained, noting that she typically only eats two meals per day, one of which is a smoothie for breakfast.

At times, she has visited her local food bank, finding that she was only able to get highly processed food there.

She is concerned that eating food with empty calories and little nutrient value will only exacerbate her health issues, driving up costs for other expenses, like medications.

What is driving the rising costs?

David Macdonald, a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), told The Maple that the current round of inflation is being driven by two main factors.

Input prices that impact the cost of goods, like gasoline and wheat, are on the rise in large part because of supply chain issues and the war in Ukraine.

The conflict is showing no signs of abating, as Western countries, including Canada, continue to send billions of dollars in weapons to Ukraine, while also pressuring the Ukrainian government against seeking a peace deal with Russia, which is continuing its brutal invasion.

Second, Macdonald explained, corporate profits play a significant role in driving up consumer prices.

“As corporations increase profit margins, and attempt to maintain them, they can also be a driver of inflation, particularly in industries where there isn't a lot of competition, where there are monopolies or oligopolies, or a concentration of corporate power,” said Macdonald.

In these cases, Macdonald explained, large companies wield pricing power not only to offset rising input costs, but also to pump up profit margins. This factor, he said, has “clearly been happening” in the most recent round of inflation.

A third factor that economists commonly blame for inflation is rising workers’ wages. However, said Macdonald, “workers wages are well behind inflation, about half of what inflation is, and so in that regard, we're actually seeing real wage losses due to how high inflation is and how low, comparatively, workers’ wages are.”

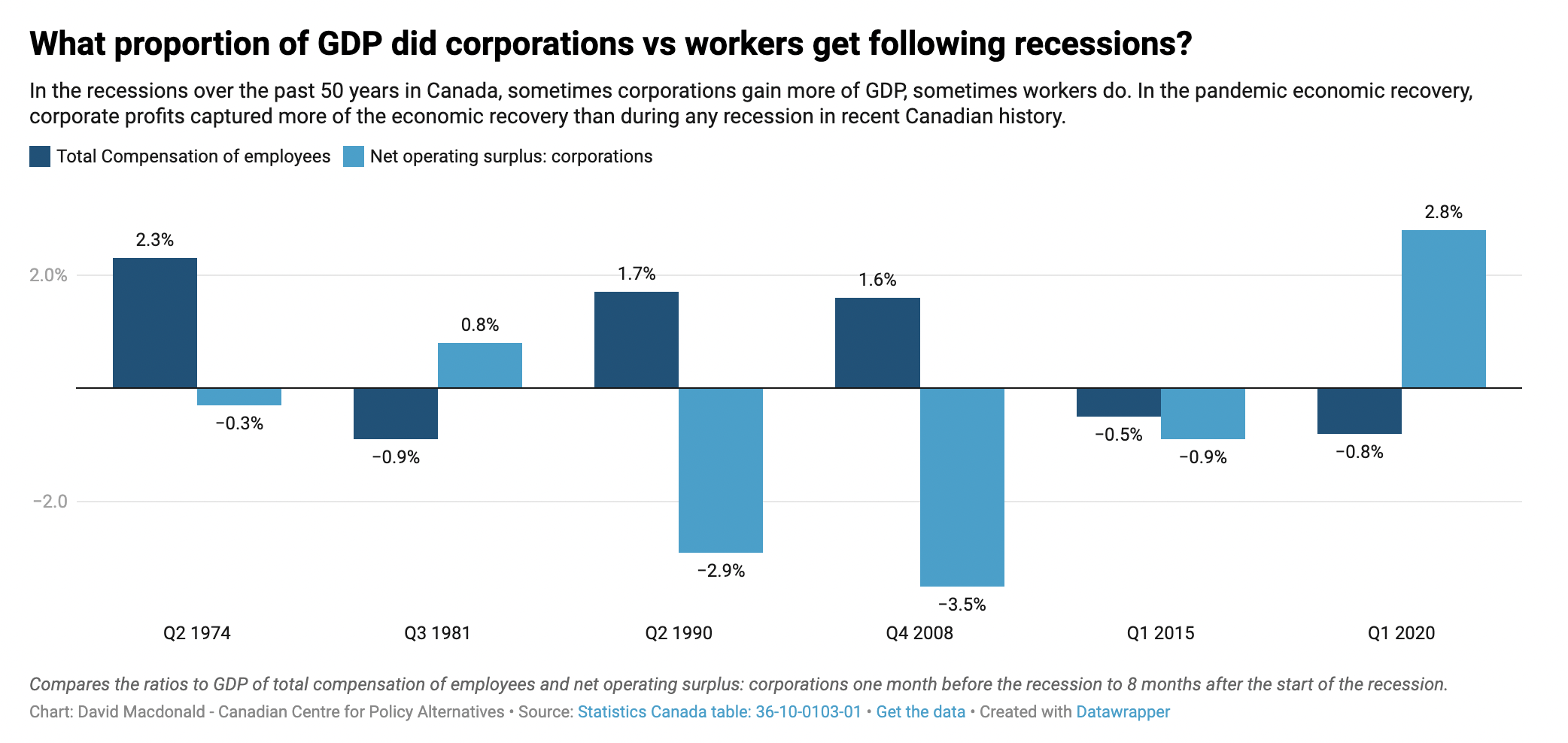

In a recent report, Macdonald compared changes in workers’ wages and corporate profits across the past six economic recessions in Canada. As a result of the pandemic recession, corporations have enjoyed a 2.8 per cent increase in net operating surpluses, while worker compensation fell by 0.8 per cent.

“It's actually unprecedented to see the corporate sector capture so much economic growth coming out of a recession,” said Macdonald.

Apart from groceries and gasoline, shelter costs have also increased. The most recent CPI update revealed that shelter costs rose by 7.4 per cent year-over-year in April, the fastest pace since June 1983.

The housing sector, said Macdonald, is an area where the federal government has a significant amount of control.

“The federal government directly regulates the underwriting standards - the insurance for Canadians to get mortgages - and so there's a lot of regulatory power that could be used there with no actual expense for the federal government,” he explained.

In a recent speech addressing inflation, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland re-announced her government’s plan to introduce a one-time $500 housing payment for low-income Canadians. For perspective, that would cover less than one-third of one month’s average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Guelph.

In terms of housing, one specific measure the government could take would be to increase the minimum amount that investors need for a down payment on a piece of property, said Macdonald. This would disincentivize investors, reducing the amount of money fuelling the housing crisis, thereby lowering costs.

On the other hand, the surge in food and gasoline prices is being driven by international factors. Short of resolving the Ukraine conflict, said Macdonald, there is little that the international community can do to address this issue.

Indeed, inflation is not confined to Canada, and is currently being seen in every major country in the world.

Domestically, the Bank of Canada could significantly increase interest rates, but doing so risks triggering a recession, Macdonald noted. In the short term, the feds could index benefit payments more nimbly so they keep pace with inflation rather than lagging behind it, and additionally create new one-time benefit payments for low-income households.

Many provincial benefits that are not already indexed to inflation could also be adjusted, said Macdonald.

Concerns for the future

However, for those living on social supports, covering basic costs was difficult even before the inflation crisis. Meanwhile, even those with relatively secure incomes are nervous about rapidly rising day-to-day expenses.

Alicia Bevan is a 26-year old psychology graduate student living in Kitchener with her partner, who works full-time in the tech sector. She said that while she is not hurting financially as much as those on lower incomes, she and her partner have recently had to budget much more carefully.

“I would never buy meat that wasn't on sale anymore,” said Bevan. “I always try to consider meatless options now.” She is also opting to cook things like Kraft Dinner more frequently than nutritious meals.

Bevan is worried that things are only going to get worse. “I think both our federal and provincial governments are extremely ill-prepared for the challenges our country is currently facing and will face in the future with regard to the security of our food chain,” she explained, adding that she will likely struggle to attain the quality of life that her parents were able to enjoy.

“I don't have the purchasing power that my parents had when they were my age, and my wages don't go as far in terms of purchasing power and quality of life,” said Bevan. In particular, she noted, the climate and housing crises are sources of tremendous stress when she thinks about the future.

The most recent Youthful Cities Real Affordability Index update found that young people aged between 15 and 29 cannot afford housing in any of the cities, big or small, that they live in.

In Kitchener, the average deficit in monthly expenses faced by young people was $842.

It’s not only young people who are grappling with soaring housing costs, however. Reynolds said she paid close attention to the recent provincial election in Ontario, and noted that the major political parties talked a great deal about homeownership.

“What about [those of] us who can't afford a home? We're seniors, and we rent,” Reynolds explained, pointing out that Ontario Premier Doug Ford removed rent controls on new units shortly after taking power in 2018.

“Now you are [trusting] that the building owners won't be unscrupulous,” she said. “That's just not logical.”

Alex Cosh is the managing editor of The Maple.

Edited by John Young.