On May 28, I received a request via Twitter from a CBC producer to speak on “The Current” about the anti-Black police murder of George Floyd, and the anti-Black experience that Christian Cooper had in New York’s Central Park when Amy Cooper called police and feigned terror after he asked her to put her dog on a leash.

When I asked if we’d talk about Canadian incidents of anti-Black policing — including the death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet in Toronto and the police killing of D’Andre Campbell in Brampton — I was told that there was no time to discuss those issues, and that the segment was focused on American racism.

During my pre-interview, I was asked what the “next steps” would be for activists, given the uprisings that were ongoing in response to Floyd’s murder. When I said it was time for society to discuss defunding the police, the producer responded with what sounded like bewilderment, and my pre-interview quickly ended. I was later told they booked someone else.

The following day, I wrote about my experience on social media in a series of posts that went viral. Those responding to my posts were rightly frustrated about what my experience meant: The CBC was not interested in having a Black person speak to an issue that would be an indictment of Canadian society, and was determined to define the parameters around which the conversation about anti-Black racism could occur on the country’s public broadcaster.

The problem is that the CBC is controlled by people who are mostly white. How could they possibly be the arbiters of what conversation was appropriate with respect to anti-Black racism in Canada?

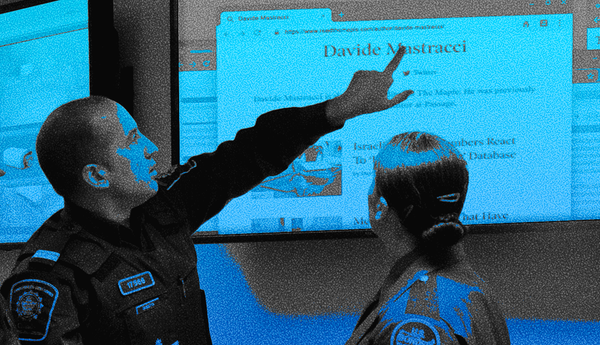

A few days later, I was providing comment all over Canadian media on the issue of defunding the police — apparently, Canadians were interested in this issue. Shortly thereafter, Canadaland shared an email with me that they’d acquired: After seeing my viral tweets, CBC had been having internal conversations about potentially asking me to appear on “The National.” They determined that I should appear at some point, but that my position of “defunding the police here in Canada” was “extreme,” and “we should acknowledge [it] as such” on the air.

Two weeks later, hindsight reveals that the CBC’s position as decreed from upper management was absurd. All over the world, various news outlets are covering the concept of defunding the police. Newsweek UK, NPR, the New York Times, the Washington Post and even conservative outlets such as the National Post are reporting and opining on the overarching demand of this iteration of the Black liberation movement.

The CBC could have been the news organization at the fore of this discussion. Instead, they were left playing catch up. How could the CBC have gotten it so wrong?

The problem is in the overwhelming whiteness of Canadian media. Because newsrooms are so homogenous in experience, the CBC had no way of recognizing that an issue outside their realm of experience and understanding could possibly be popular. This incident reveals that the CBC is failing to serve a vast portion of the public in its role as public broadcaster. It also demonstrates the media’s power to arbitrate the knowledge that Canadians get exposed to, and the resulting public conversations that we have as a society.

I’m by no means suggesting that this is an issue unique to the CBC. Plenty of news media outlets have embarrassed themselves the last couple weeks with their coverage, with varying degrees of consequences.

Various headlines tackled the historic worldwide uprisings against anti-Blackness with the most senseless and underdeveloped analysis one could possibly imagine by asking the absurd question, “Does racism exist in Canada?” How could media in a country where the prime minister was recently embroiled in a Blackface scandal, where a province implemented a ban on religious symbols and where scores of Indigenous communities still do not have access to potable drinking water seriously ask such a question?

On June 1, the National Post published an asinine column from Rex Murphy opining that anti-Black racism was, in fact, not a problem in Canada. The next day, former Conservative Cabinet Minister Stockwell Day appeared on CBC’s “Power & Politics,” likening anti-Black racism to his experience being bullied as a child who wore glasses (why these white men would be invited to speak on these issues, I have no idea).

Predictable comparisons to the United States were cited as reasons for concluding that Canada didn’t have a problem with anti-Blackness. These comparisons weren’t based on data or anything more than what I can only assume is a really good feeling of what it means to be Canadian and a consistent refusal to believe that Black people know what we’re talking about when we articulate our experiences.

A June 12 Toronto Star editorial pit Black people against Indigenous people in its discussion about violent policing, arguing that those who were angry about anti-Black policing needed to “save some of their ire” for Indigenous people, as if to suggest that one couldn’t understand that the issues of brutalization against Indigenous and Black people are part of the same structure of anti-Blackness and colonization that inflicts violence against our communities.

These pieces, denying the direct experience of hundreds of thousands of Black people living in Canada, only add to the strife that we’ve had to endure these past weeks, in addition to bearing witness to more incidents of anti-Black policing in the news.

The media functions as an arm of Canada’s brand of anti-Blackness: denial. In asking the question, “Does systemic racism exist here?” the media affords the opportunity for politicians and police operatives to deny its existence. The failure of the media to hold these powerful people to account for their activities allows their anti-Black and -Indigenous violence to continue.

When journalists fail to ask those in power to account for why Black people in Ontario are 20 times more likely to be killed by police than non-Black people, or why Black people in the province are far more likely to be carded, the media participates in the police public relations narrative that is disconnected from documented reality.

Allowing Toronto Police Chief Mark Saunders to simply address the existence of anti-Black racism without accounting for the violence his force inflicts on Black people is an abdication of journalistic responsibility. When Rosemary Barton, CBC’s chief political correspondent, asked RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki about whether racism exists in the force, and failed to follow up with questions about the actual impact of its racism on Black and Indigenous people, she allowed the CBC to participate in the routine denial of the experience of the most oppressed people in this country.

At best, this sort of coverage excludes a large portion of the audience in Canada. At worst, it encourages the police to continue using violence against our communities. Police institutions know they can get away with killing us. And people with political decision-making power know that they can get away with inaction on the problem. They’ve been doing it without the appropriate ire or consideration of the media for decades.

The media’s refusal to engage in issues of life and death for Black people has delayed a national conversation on the way that we provide safety and security in our society for far too long. The fact that Black people have to organize hundreds of thousands of people to take to the streets in protest of police brutality for the media to consider finally engaging with the issue is an embarrassment.

The past couple of weeks makes it abundantly clear that Canadian mainstream media is currently not qualified to discuss the issues that Black people need to be part of the public political discussion in this country. The fallout has been severe.

Articles were retracted in a manner that prevents readers from seeing what was originally published. CBC “The Weekly” host Wendy Mesley was suspended for her use of “careless” language. Christine Genier, the Indigenous host of the CBC’s “Yukon Morning” radio show, made a statement on air about the constraints of her position as a reporter before submitting her resignation. Black, Indigenous and otherwise racialized journalists and producers took to social media to discuss their experiences of anti-Black racism, anti-Indigeneity and racism in Canadian media.

There are talented Black journalists in Canada. Why are they systematically being shut out of newsrooms and production teams? Their absence creates the gaffes that Canadian media stepped in throughout this crisis.

In the wake of the police killings of Chantel Moore, Rodney Levi, D’Andre Campbell and Regis Korchinski-Paquet, some of Canada’s most talented freelance journalists in the Black community were eventually given platforms to write about these issues. Yet they should be part of the power structure of Canadian newsmedia, and part of the team that decides what is newsworthy and how an analysis should be approached.

If Canadian media is serious about reckoning with its anti-Black racism and its resulting inability to responsibly report on issues of importance to the Black community, it needs to take a deep and critical look inward that acknowledges an unavoidable truth: Canadian newsrooms are far too white, and Black and Indigenous communities suffer as a result of their inadequacy.

The next step is taking action, meaning some of the powerful white elites at Canadian media institutions will need to vacate their positions, and make way for the talented Black journalists who are routinely sidelined to take up power.