For a group of journalists and scholars, the “Nazigate” scandal in Parliament back in September seemed an entirely predictable outcome of a broader movement that, they argue, has distorted realities about the Holocaust for decades.

While the story has largely disappeared from international news headlines over the past month, those same journalists and scholars warn that the factors that made such a scandal possible remain deeply entrenched in the Canadian government and civil society.

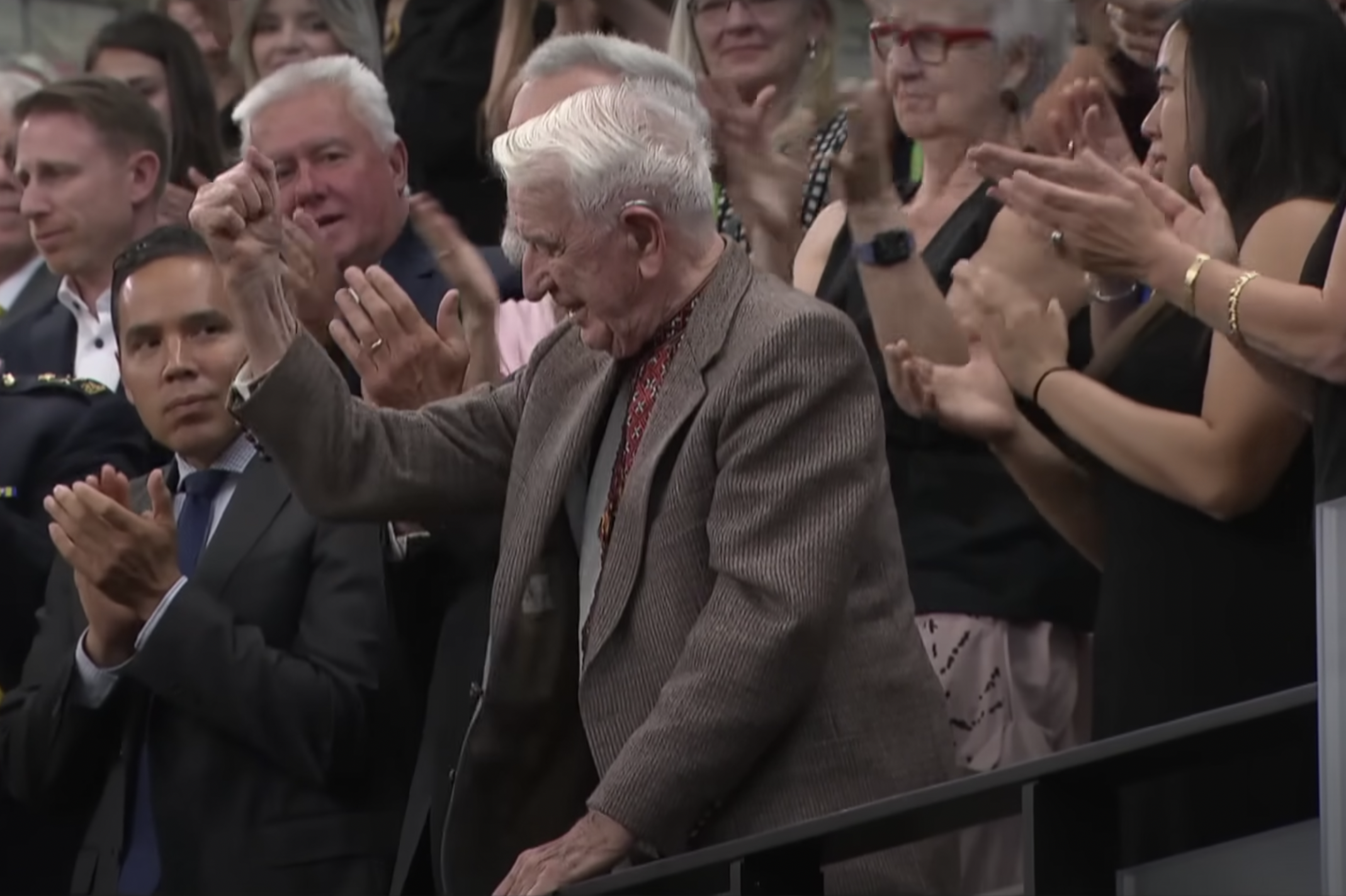

In this article, we explore the history leading up to the moment when the House of Commons gave a standing ovation to Yaroslav Hunka, a Waffen SS veteran who was introduced as having fought against the Russians during the Second World War.

Some historians see public commemorations that ostensibly recognize victims of both Nazism and communism as part of the problem.

‘Nazigate’ Media Fallout

Following the “Nazigate” scandal, some media commentators and public officials downplayed its significance and suggested that Hunka’s unit, the 14th Waffen SS Division, commonly referred to as the “Galicia Division,” was innocent of any war crimes.

On October 2, Politico ran an op-ed that suggested the public has been “conditioned” to believe that the Waffen SS’ primary task was committing genocide and claimed that describing every SS veteran as a criminal is an oversimplification of history. In 1946, the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg declared the entire Waffen SS to be a criminal organization.

The Politico article echoed longstanding sentiments held among some nationalist Eastern European diaspora groups in Canada. To this day, monuments in Edmonton and Oakville honour veterans of the Galicia Division.

These venerations are typically justified by the fact that the veterans were nationalists who wanted to fight the Soviet Union. This narrative generally equates Nazism and communism as two equally deadly ideologies, and is reflected in “Black Ribbon Day,” also known as the “Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism.”

It is an officially recognized public commemoration in Canada, but derided by critics as a negligent act of antisemitism and historical distortion for which the Canadian government bears considerable responsibility.

‘Double Genocide Theory’

Historians and scholars have argued that Black Ribbon Day is inextricably linked with a revisionist historical theory known as the “Double Genocide Theory.” Advocates of this theory argue that the people of Europe suffered from two genocides: The first committed by the Soviet Union and the second by Nazi Germany.

The idea asserts that the people of Eastern Europe were caught between two equally tyrannical and genocidal superpowers, and that the genocide of the Jews by the Nazis came after the Soviet Union committed a genocide against the predominantly Christian population of Western Ukraine.

Black Ribbon Day is recognized by Canada, the United States and the European Union on August 23, the day that the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany was signed in 1939, and a little more than a week before the Nazis invaded Poland, starting the Second World War.

Critics say the problem with the Double Genocide Theory is twofold. First, it insinuates that the Holocaust was predicated on an earlier Soviet-led genocide. Second, by drawing a false equivalence, it trivializes the near universally accepted importance of the Holocaust as a genocide that is generally considered to be in a category of its own.

The industrialized mass murder of Jews in Europe via slave labour and death camps came about only after nearly a decade of state-sponsored dehumanization of the Jewish people by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. This genocide built on centuries of antisemitism that had been normalized by political and religious leadership, particularly the Roman Catholic Church.

No nation acted to prevent the genocide that was clearly going to happen, not least because of pervasive antisemitism and the common association of Jews with Bolshevism. When Jews came to Canada seeking asylum in June 1939, mere months before the Nazis invaded Poland, the Mackenzie-King government turned them away.

Roughly one in four Jews murdered during the Holocaust were killed with bullets, often by neighbours, with weapons handed out to local collaborators by the Nazis as they invaded the Soviet Union beginning in the summer of 1941. This happened before the “Final Solution” was adopted as official Nazi policy at the Wannsee Conference of 1942.

Even before Auschwitz and Sobibor began operating as extermination camps, Hitler found willing participants to carry out his plan among local fascist collaborators that emerged from the Baltics to the Balkans and the Black Sea.

Nearly all modern, international, legal understandings of human rights are themselves a consequence of the Holocaust. The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights — and all the legislation, policies, laws and related declarations that have come since — stated that it was conceived because of the Holocaust.

Among mainstream professional historians, the enduring consensus is that no other genocide in human history has affected as many people, been so destructive, reached such levels of unimaginable horror, or has been as impactful, as the Holocaust. In fact, to deny or distort the reality of the Holocaust is a crime in many countries.

The idea that the Holocaust was a reaction to earlier Soviet-led crimes, a position held by some commentators such as Askold Lozynskyj, a New York attorney, president of the Ukrainian Free University Foundation, and formerly president of the Ukrainian World Congress between 1998 and 2008, is highly criticized. The theory primarily refers to the Holodomor, the mass starvation, primarily of ethnic Ukrainians, during the Soviet famines of 1931-1933.

The Holodomor is considered to be a genocide by many historians and national governments, including Canada. However, the Holodomor is not generally considered to be a genocide of equal magnitude to the Holocaust.

Further, there is a substantial scholarly debate on whether the Holodomor fits the legal definition of a genocide. Stephen G. Wheatcroft, regarded by some as the foremost international expert on Soviet agricultural policies of the interwar period, has argued that while Stalin was criminally responsible for exacerbating the crisis, brutalizing peasants, and covering up the incompetence of the state and its agricultural and economic policies, the Holomodor was fundamentally accidental. The undisputed consensus among historians is that irrespective of the specific genocide debate, the Holodomor was a crime against humanity.

The problem, according to historian Dovid Katz, with the implicit argument of Black Ribbon Day and the Double Genocide Theory — that the Holocaust was predicated on the Holodomor and that they are equivalent genocides — is that this is based on the antisemitic myth of Bolshevism being a Jewish conspiracy.

In an interview with The Maple, Katz explained that far-right, ultranationalist, Eastern European historical revisionists are “obsessed” with revising the history of the Holocaust and Second World War by way of “a number of cunning ruses.” He explained:

“A new far-right inspired revision of Second World War history, known as Double Genocide, was being slowly but surely insinuated into an unsuspecting and naive West via endless East European state sponsored conferences, resolutions and commemorations which all share one common denominator: To formally, and as a matter of sacred principle, ‘equalize’ Nazi and Soviet crimes in the spirit of postmodernist mush and for the purpose of relegating the Holocaust to some kind of secondary reaction to the ‘first genocide’.”

Historians, and scholars interviewed for this article – including Katz, Per Anders Rudling (an expert on Ukrainian ultranationalist collaborators) – all pointed out that the first stage of the Holocaust began with the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, before the Wannsee Conference of 1942 when Hitler invoked the “Final Solution” for the murdering of Jews in Europe.

A consistent aspect of this phase of the Holocaust was enthusiastic support for the Nazis among the nationalist elements of the remaining local populations, despite many of these having no connection to the Holodomor or the Soviet famines of 1931-1933.

The Emergence Of Black Ribbon Day

Commemorating Black Ribbon Day in Canada goes back at least as far as 1986. At the time, the new policies of glasnost and perestroika were opening Soviet society to reform, but this also brought about new challenges to Soviet authority by various ethnic communities within the union and its sphere of influence.

Long unanswered or repressed historical questions began to be asked. In a nearly simultaneous mirroring of what was occurring in the Soviet Union, North Americans began to ask hard questions of their own governments, particularly on the highly controversial and emotionally charged issue of alleged war criminals from Eastern Europe who had found refuge in Canada and the United States.

However, while the Americans created the Office of Special Investigations under the Justice Department in 1979, there was far less interest in investigating similar claims of war criminals having found refuge in Canada after the war. In fact, some researchers recall rumours of former Nazis freely wandering the streets of Canadian cities.

Alvin Finkel, emeritus professor of history at Athabasca University, told The Maple of a peculiar memory from his childhood growing up in the north end of Winnipeg.

Finkel recounted that his father pointed out people on the street, claiming they had fought with the SS, or had otherwise collaborated with the Nazis. Although it didn’t mean much to Finkel as a child, as an adult it sparked his curiosity.

When Finkel began investigating the matter in the 1980s, he found substantial, albeit heavily redacted, records at Library and Archives Canada, and published an article on his findings in the Journal of Canadian Studies. But the newspapers weren’t interested.

“The Globe and Mail told me that they'd already published on this, which was a lie,” said Finkel. “There was a little more honesty [from the Edmonton Journal], saying that they didn't want to offend the Ukrainian community in the city.”

When prime minister Brian Mulroney convened the Deschênes Commission to finally investigate the matter in 1986, the commission was hamstrung. As explained by Karyn Ball, a University of Alberta professor who specializes in historical memory and the Holocaust: “They set the parameters so narrowly for their investigation of criminality [of the Waffen SS], that they basically blocked out all the crimes that were committed by Waffen SS members before they joined it.”

While some collaborators on the Eastern Front joined the SS directly, others volunteered for a wide variety of other Nazi military units, including auxiliary police, some of which were later reformed as SS units. Roman Shukhevych, who had led the Nazi-allied Ukrainian Insurgent Army, had previously commanded auxiliary police units of the wartime German army.

Per Anders Rudling explained in an interview with The Maple that commemorating Black Ribbon Day also coincided with the John Demjanjuk ordeal in the United States.

Demjanjuk was a Ukrainian-American autoworker who came to international attention in the mid-1980s when he was deported to Israel to stand trial for his actions as a death camp guard during the Second World War. Rudling noted that in a 1986 edition of Ukrainian Weekly “the promotion of Black Ribbon Day shares editorial space with tributes to Demjanjuk, on how to raise money for him, and even an ad on how the ‘Ukrainian nation is on trial in Israel.’”

Demjanjuk was ultimately convicted in 2012 as an accessory to mass murder while he was a death camp guard at Sobibor.

Support for Demjanjuk represented part of a larger trend. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of communism in Eastern Europe ushered in a new era of nationalism, as well as new opportunities for historical revisionism. In the 30 years since, a small cadre of far-right ultranationalists with particular influence both in Eastern Europe and on the international stage, have, as Katz explained, “elevated some of the most brutal and prolific collaborators and perpetrators of the Holocaust to the status of national hero on the grounds that they were ‘anti-Soviet activists.’”

Shukhevych, a Ukrainian Nazi collaborator responsible for the murders of tens of thousands, and who is commemorated with a monument in Canada, is one of the better known examples of this phenomenon.

Meanwhile, the Progress Report revealed last month that the University of Alberta’s Canadian Institute for Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) received donations and endowments worth $1.4 million in the names of Ukrainian Nazi collaborators. David Pugliese at the Ottawa Citizen reported this week that a panel to discuss the Waffen SS was quietly cancelled at the university after professors complained that the CIUS continues to engage in whitewashing Nazi crimes.

As Canadians are now acutely aware, some suspected Eastern European collaborators found postwar refuge in Canada precisely because they were considered reliably anti-communist.

Katz and Rudling believe that there are legitimate victims of communism, and that they ought to be commemorated, as a specific day of recognition provides an opportunity to educate and discuss the nuances and details of the historical record.

But Black Ribbon Day, they said, is too sullied by deliberate efforts to obfuscate historical reality to be of any use.

“It is high time for Canada and the other leading democracies to establish a day to commemorate communism’s victims,” said Katz. “It is time to relegate Black Ribbon Day to the proverbial dustbin, and to understand that efforts to downgrade the empirical reality of the Holocaust’s genocide must be resisted.”

Taylor C. Noakes is an independent journalist and public historian from Montreal.

With files from Alex Cosh.

Member discussion